God’s bollocks, but this might just be my favourite fantasy novel of the decade.

Lev Grossman’s The Bright Sword is not just another Arthurian retelling for the modern generation. Nor is it your average knight’s tale or a study of the Camelot era in Great Britain. It’s a literary reckoning with myth, masculinity, belief, and Britain itself, sitting square between a medieval fever dream and a postmodern meditation on traditional storytelling.

Your cue that The Bright Sword will not be like other King Arthur books lies right on the Chapter One Title Page. Grossman chose to include the quote: “Strange women lying in ponds distributing swords is no basis for a system of government.” You may recognise the line from Monty Python and the Holy Grail. The tone and style of that film informs a lot of The Bright Sword’s more comical elements, and its context added a post-modern, tongue-in-cheek element to my first reading.

The Bright Sword is strange, sacred, silly, and sad—a curious combination. After I finished it, I wanted to kneel before a grail by an enchanted pond and ask nothing but to read it again for the very first time.

Unfortunately, I had to settle for writing a review on the internet, instead. So let’s jump into the dark but eerily shimmering waters of the latest novel from the author of The Magicians series. Be warned, minor spoilers will ensue!

A Dream of Britain, Reforged

The legend of King Arthur came to be very slowly, over centuries. From a historical standpoint, there’s no conceivable way he could have existed—and if he did exist he wouldn’t have been a king, nor would he have pulled a sword from a stone or been blessed with miracles and visitations from angels.

But The Bright Sword takes over a thousand years of British history, picks out the best parts, and sets its tale in an uncertain age where anything seems possible. Because of that we get a Round Table in its prime, its decline, and aftermath.

The novel is meticulously researched, overflowing with authentic historical details, but plays fast and loose with the ages and backgrounds of certain historical figures and countries. It’s messy and full of contradictions and anachronisms, but, as Grossman states in his historical afterword, the messiness is “an authentic part of the Arthurian tradition”.

We aren’t here to build a new fantasy world, we’re here to delve into the most delightful parts of the old one, of dreamlike medieval Britain where days and months and reason have no meaning, only the quest.

The Bright Sword is a woven tapestry, the greatest hits of one of our greatest legends as you’ve never heard it. Time ebbs and flows, dreams come and go, and by the end it feels as though you’ve lived an entire life, or several.

Magic, Madness, and the End of an Age

In conversation regarding the tones and themes of The Bright Sword, there are several key texts I’d like to draw comparisons to. Unexpected and apparently unrelated, perhaps, but bear with me, and I promise they’ll make complete sense.

The Red Dead Redemption Angle

Hear me out: The Bright Sword is kind of like the British version of Red Dead Redemption II—the last days of the (English) Wild West, the great years of magic and madness and freedom. I don’t use this comparison lightly, nor do I choose it merely because both stories feature a middle-aged man named Arthur and a merry band of knights/cowboys.

Rather, the two texts lie side by side in tone and theme, in the gradual and mournful unraveling of a great dream.

In Red Dead Redemption II, the Van der Linde gang clings to their crumbling vision of freedom and outlaw honour, all the while battling the encroaching modernity that will render them obsolete.

“This place… ain’t no such thing as civilized. It’s man so in love with greed, he has forgotten himself and found only appetites.“

— Dutch Van Der Linde, Red Dead Redemption II

In The Bright Sword, the surviving Knights of the Round Table grasp at their memory and belief in Arthur’s vision (and God’s intervention), as their precious Camelot grows ever colder, cynical, and godless.

Unfortunately, both Arthur Morgan and Arthur Pendragon are doomed by the slow death of the stories they represent, that they are at the centre of. The Van der Linde and Round Table gangs are fractured, flawed, and human.

Some of them are unfettered drunks. Some dream of simpler worlds. Some are in love with ghosts and memory and shun the present and future. But all feel the fading warmth of the sun setting on their golden days.

Arthurian Myth vs. The Third Age of Middle-Earth

The elegiac (and elegant) tone of The Bright Sword is also aligned with The Lord of the Rings, if in nothing else then by Faramir’s unforgettable words in The Two Towers (novel):

” ‘For myself’, said Faramir, ‘I would see the White Tree in flower again in the courts of the kings, and the Silver Crown return, and Minas Tirith in peace. Minas Agor as of old, full of light, high and fair, beautiful as a queen among other queens, not a mistress of many slaves. War must be, while we defend our lives against a destroyer who would devour all; but I do not love the bright sword for its sharpness, nor the arrow for its swiftness, nor the warrior for his glory. I love only that which they defend: the city if Númenor; and I would have her loved for her memory, her ancientry, her beauty, and her present wisdom. Not feared, save as men may fear the dignity of a man old and wise.’ “

— J. R. R. Tolkien, The Two Towers

Like The Bright Sword, Tolkien’s most famous Middle-Earth tale takes place in the twilight of a great era. After battling against Sauron and Saruman’s industrial-esque conquering, the Fellowship’s quest to destroy the One Ring comes with a grave consequence: the end of the elves’ time in Middle-Earth. Similarly, the bulk of the (present-day) narrative in The Bright Sword occurs after the age of miracles, when magic (and God) has forsaken Britain.

The Last of… The Round Table Knights

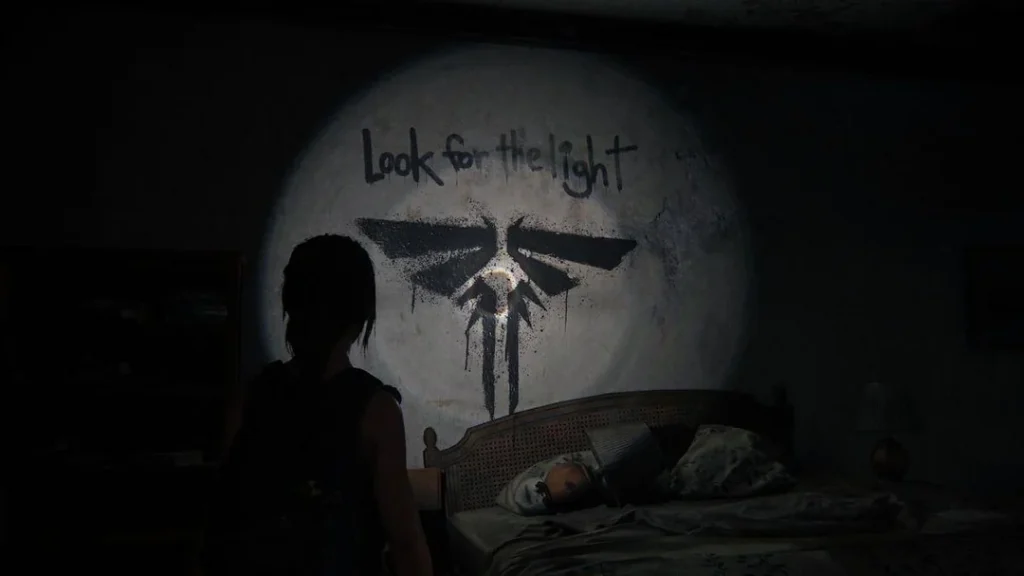

Grossman has stated that both the Max television show and video game versions of The Last Of Us heavily influenced The Bright Sword. As an avid player of both Last of Us games, I wouldn’t have even thought of that, but Grossman connected those dots for me, tapping into my favourite genre ever: the post-apocalypse.

Like The Last Of Us, The Bright Sword takes place in a disastrous wasteland where the worst has happened. Joel’s flannel-driven stoicism and Ellie’s youthful snark may not be the most Arthurian of archetypes. But the very nature of the first game/season’s story—that of two knights errant traveling the world in search of a miraculous solution to the state of the world—is one of the strongest and most recognisable myths there is, and it’s exactly what the Grail Knights of the Round Table seek in The Bright Sword. They look to the light.

“We’re about to hit a milestone in human history equal to the discovery of penicillin. After years of wandering in circles, we’re about to come home, make a difference, and bring the human race back into control of its own destiny. All of our sacrifices and the hundreds of men and women who’ve bled for this cause, or worse, will not be in vain.” — Jerry Anderson, The Last Of Us (2013)

So What Do These Comparisons Mean?

The point is that by the end of all four tales, the viewer/reader/player is forced to confront the truth of progress and advancement. The other side of the promise of a bright and peaceful future is the disappearance of a wild and authentic freedom. Should they toil in the dark hoping for miracles or accept that the world will move on with or without them?

We then have to ask: is progress, at its core, a reflection of the unending struggle between the desire for individual emancipation and the demands of a collective order? In that case, what’s even the point of being an individual at all?

‘A Novel of King Arthur’ — And Everything Else, Too

I must confess that I’ve never been much of a fan of the way Lev Grossman books have been marketed. I still remember my first copy of The Magicians, adorned with an unsightly, irremovable sticker that bore the witless slogan: “Harry Potter for grown-ups.” Identically worded, Buzzfeed’s article about the television adaptation was titled ‘This New Syfy Show Is “Harry Potter” For Grownups‘.

In 2024, The Bright Sword was heralded by publisher Penguin as ‘The first major Arthurian epic of the new millennium’.

The subtitle on the paperback even reads ‘A Novel of King Arthur’. While that’s not technically untrue, it does The Bright Sword an injustice to omit everything else it is about and boil it all down to King Arthur.

Sure, King Arthur is talked about a lot. He’s present in nearly every chapter by name. But he’s very rarely the centre of the narrative. Instead, he’s the sun around which many other smaller stories orbit. Instead, we spend our time with the men and woman who followed him, disappointed him, loved him, betrayed him.

Grossman is more interested in the fragments and contradiction of the Arthurian legend than presenting a single defined narrative. He plays with the messiness, the apocryphal, the unanswered questions. He doesn’t reimagine the myth but instead interrogates it, asking us what we need from a story of Arthur right now—at the end of the 21st century’s first quarter. What do we want from kings, from divinity—from Britain?

So, sure, The Bright Sword is a ‘A Novel of King Arthur’. And if that’s what draws in the masses, so be it. Because we need novels like The Bright Sword. We need tales that are unafraid to be unapologetically true, and fantastical, and imperfectly human.

The Bright Sword vs. The Once and Future King

It’s inevitable to draw comparison’s between Grossman’s contemporary epic and the original Arthurian retelling by T. H. White: The Once and Future King.

The Once and Future King is a classic myth retelling that culminates in Arthur’s death and the fall of Camelot. Its emphasis is on tragedy and the cyclical nature of history.

On the other end of the spectrum we have The Bright Sword and its exploration of the dilemmas of attempting to rebuild a fractured kingdom through mythic quests and the revitalisation of miracles. It explores not Arthur but the lives of those who must endure in a world without him.

In Lev Grossman’s own words: “One of T.H. White’s strokes of genius was to tell the story of Arthur’s childhood. No one had ever done that before — he filled in a blank space on the map. Part of the point of The Bright Sword is to explore another blank space: the one after Arthur’s death.”

The Bright Sword Makes Us Root for the Underdogs

In The Bright Sword, a ‘novel of King Arthur’, Arthur isn’t actually our hero. Nor is Lancelot, considered the greatest knight of all time. Not even Galahad, a knight of virtue and purity. They’re actually, to a certain extent, the antagonist.

And instead, our protagonist is a completely unknown young man named Collum, who hails from an unknown land from an unknown father. But he’s driven by his belief in King Arthur and what Camelot can be and mean for the world.

Unfortunately, he’s too late. Camelot has fallen, and Arthur is (probably) dead.

Collum is supported by a cast of broken knights, third-tier names that you probably haven’t even heard of: Sir Bedivere, Sir Dagonet, Sir Palomides, Sir Dinadan…

Grossman breathes life into these has-beens and could-have-beens. They aren’t the champions of the bright, shining kingdom. They’re the ones left behind when the well of miracles dry up. They still fight, love, and mourn, and carry the story forward.

Let’s Talk About Those Interludes

The Bright Sword takes several lengthy breaks from the primary narrative, dripped here and there throughout the acts. Some stand alone, while others continue on from previous sections. Almost all of them centre around a chosen knight of the Round Table, offering us a window to their mind, their past, outside of Collum’s (and Arthur’s) story.

The Bright Sword is split into four books. Throughout Book I, ‘A War of Wonders’, we get a three-part tale of Sir Bedivere, Arthur’s right-hand man who happens to also be madly in love with his king. Scattered throughout Book II, ‘A God of Sand and Dust’, are two chapters of Sir Palomides, one of Sir Dinadan, and three of Sir Dagonet and Sir Constantine, who serve as a duo. Book III, ‘The Blind Giant’, offers us chapter-length backstories for Nimue, Merlin’s ex-apprentice, and Sir Scipio, a Roman legionary who winds up sleeping through the fall of his empire.

By book IV, ‘The Saxon Shore’, we’ve run out of Round Table knights, and Grossman instead offers us his first (and only) Arthur-centric chapter titled ‘The Night Office’. After the decline of miracles and the abandonment of the Quest for the Grail, Arthur discovers the way forward, or at least tries to:

“Understanding was filling Arthur as if from a miraculous spring. Britain itself was a wounded land, cloven in two, British and Roman, pagan and Christian, north and south, old and new. It was born in blood, divided eternally against itself, its different natures so mixed it could never extricate itself from itself. No miracle would heal that wound either. But Britain would heal, all on its own, slowly, the hard way, if only he would let it. It would always be a scarred land, a complicated land, but complicated was not the same as broken. It would never be pure, no more than that Grail in the circle was pure. It would not be perfect. But it would be whole.”

What’s the Point of Breaking Up the Story?

Some readers may dislike or straight up hate these lengthy interludes for breaking up the main narrative. But I argue they’re just as necessary. The Bright Sword is a rather long, episodic novel, after all.

Think of a big-budget HBO (or are they calling it Max, now?) show that has whole episodes from the POV of side characters. We get history, world-building, and backstory—and it makes key character moments shine all the brighter while offering tonal variety and putting us in a different character’s shoes. In this sense, Grossman’s The Last of Us inspiration really shines.

These interludes aren’t distractions. They’re vital organs of the book. They humanise the legends. Each reads like a confession or a prayer, a whispered tale told by a dying fire. They’re more introspective and somehow slower, despite often skimming over many years in a single paragraph.

These are the secrets of the Knights of the Round Table. They offer clarity and reflection and invite the reader to consider: what happens when your story isn’t the one written down? These interludes offer us the opportunity to not just read about a glorious age but to eavesdrop on the people who had to survive it.

Sir Dinadan, the Knight of Becoming

The most significant of these Round Table interludes, to my mind, is Dinadan’s. Lev Grossman portrays the knight—most known for his role in the tragedy Tristan und Isolde—as a transgender man who uses his armour to hide his female attributes and present his true identity as a knight.

This choice could easily have been ill-advised but it’s executed alarmingly well. Dinadan’s identity becomes an inextricable thread in the novel’s central idea: that we’re more than the stories others tell about us—even more than those we tell about ourselves.

Dinadan (birth-name Orwen)—after years of insisting to be included in ‘boy’s games’—makes a deal with the fairies to be able to fight like a knight, thereby becoming one. The chapter concludes with Dinadan escaping an arranged marriage and accepting the price for his fairy training, that being to kill Merlin (this pays off in a big way during the novel’s climax). It’s this sort of impossible, morally knotted task the makes The Bright Sword so special.

The last line of Dinadan’s story reads: “and he would be happy, because at long last he’d done what he always dreamed of doing. he’d turned into what he already was.“

Add to the fact that Grossman’s son came out to him as trans while he was writing the novel, and Dinadan’s role in the story is all the more relevant and touching.

Purple(ish) Prose and a Kindle Revelation

I had an excellent experience reading The Bright Sword, owing in large part that it was the first book I ever read on my Kindle. As a hardcopy purist and collector/amasser of heft hardcover tomes and boxes of comic book issues, it took a lot of adjusting, and I missed the feel of paper on my fingers.

But the Kindle’s saving grace is its ability to highlight select words and phrases and instantly provide definitions and Wikipedia searches, in-text, while reading. If I was reading The Bright Sword in paperback (which I do have plans for), I would’ve been on my phone twice a page searching up place names, obscure kings and deities, and archaic language.

While I must admit that at times Grossman’s prose can err on the purple side, it’s also responsible for expanding my vocabulary and sending me down historical and mythological rabbit holes with every unknown word. So for this, I applaud The Bright Sword for its consistently literary trappings.

Make no mistake, even more so than the Magicians trilogy before it, The Bright Sword is dense. It’s complicated. It’s long. Its cast of characters, many with similar, archaic names, threatens to grow beyond even the amount of people you know in real life.

But for those reasons exactly, The Bright Sword triumphs. It’s propelled by its modern sensibilities, a healthy dose of self-awareness, the way the prose dips into the stray thoughts and imaginings of its protagonists, its detailed descriptions of battle techniques and British landscapes, and its complete and utter wild unpredictability…

The Bright Sword made me smile like no other book has in recent memory, because it feels complete. It’s dark when it needs to be and hilarious when it wants to be. It’s historically sound throughout while being unapologetically ridiculous.

Bonus: Favourite Quotes (From My Kindle Highlights)

There is something incessantly, endearingly quotable about Grossman’s prose and dialogue in The Bright Sword. Here’s a (supposedly) small list of my favourite lines, whether profound, humorous, or just neat writing. These, I highlighted with unbridled glee while reading, making good use of my new Kindle.

- He could chill his soul down to the temperature necessary for the sacrifice of loyal men.

- Vast tides of words, both familiar and strange, written and spoken, ebbed and flowed and sloshed around the marketplace as if it were a great verbal ocean.

- “With Arthur and Galahad running around I don’t know why people even bother having legitimate children anymore,” Dagonet said. “Bastards are clearly the superior product.”

- When you were inside them adventures happened slowly, but the aftermath of a failed adventure was even slower. On the journey out they’d walked in a dream, pulled on by the quest, driven by their divine purpose, but now they just trudged. It was not a path to glory, or to anywhere really, it was just a lot of cold gray mountains in northern Pictland.

- Dagonet was amazed once again at how unfailingly the world taxed people with the very thing that would try them the most.

- “Of all the animals,” she said, “only man can feel a despair that is beyond his power to endure.”

- “Two knights against one,” Palomides said, “is neither fair nor square. It is at best triangular.”

- “Can’t have an owl running around in a knight’s body.” Collum agreed that one absolutely could not have owls running around in knights’ bodies.

- She was one of those vibrant people who seemed to be part of a more interesting story than he was, and when she left she took it with her and left him behind in the dreary margins. She, the damsel, was the hero, and he the foil, soon discarded and forgotten.

- But of course it wasn’t over. Why would the future be simpler than the past? Stories never really ended, they just rolled one into the next. The past was never wholly lost, and the future was never quite found. We wander forever in a pathless forest, dropping with weariness, as home draws us back, and the grail draws us on, and we never arrive, and the quest never ends. Till the Last Day, and maybe not even then. Who knows what stories they tell in Heaven.

- They lived in a warm, safe world wrought of old gold, rich with strength and love and fellowship, where evil was great but good was greater, where God was always watching, and even sadness was noble and beautiful.

Final Thoughts—We Are the Misfit Round Table Knights (And Nimue)

Look, The Bright Sword probably isn’t for everyone. It’s not a thrilling page turner. It isn’t a historical retelling of the King Arthur myth. It’s not even a standard knight’s tale fantasy.

It is an immersion into the beauty of language and the magic therein. It’s for those who love to bathe in the dreams of kings and wizards. To find safe haven in characters that provide an anchor in a maddening sea of chaos. To become lost in otherworlds, never knowing if they shall return.

Grossman spent 10 years writing The Bright Sword, and the amount of care, respect, and passion that has gone into it is evident from the first page. It tells new tales and incorporates new ideas into a pantheon of Arthurian legend, broaching contemporary issues in ways that feel natural and inclusive instead of preachy and forced, like some other contemporary texts. Grossman deconstructs myths of heraldry and the concept of the knight’s tale, while giving us a story that embraces both.

The best part about The Bright Sword is how it pulls us, the reader, into the ragtag band of discarded Round Table Knights. We are the losers and misfits and we are the heroes and kings. We are all part of the story of humanity, and we all shape it, some more or less heroically than others. But we all stumble along through our lives, into other worlds and times, figuring out as we go, as best as we can.

As a longtime fantasy buff, I cannot recommend The Bright Sword enough. It’s not only worth reading—it’s the reason to read fantasy at all.

Enjoyed this post? Why not subscribe to the newsletter, or as I like to say, enlist in the guild? Simply add your name and email and I'll make contact when the next post is ready. Until then, cyberspace adventurer...