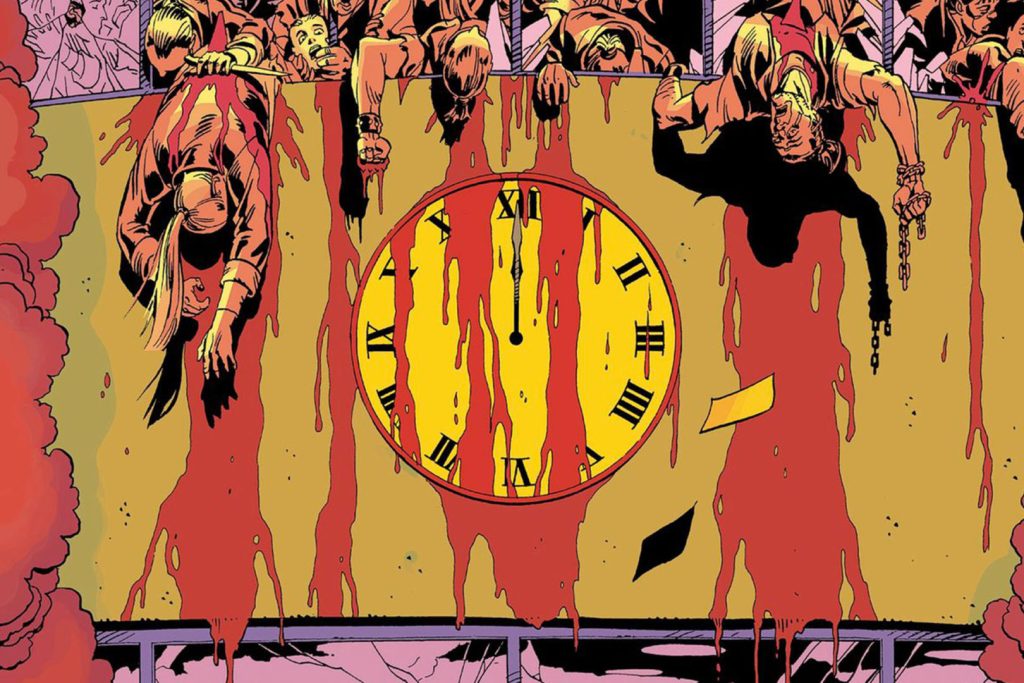

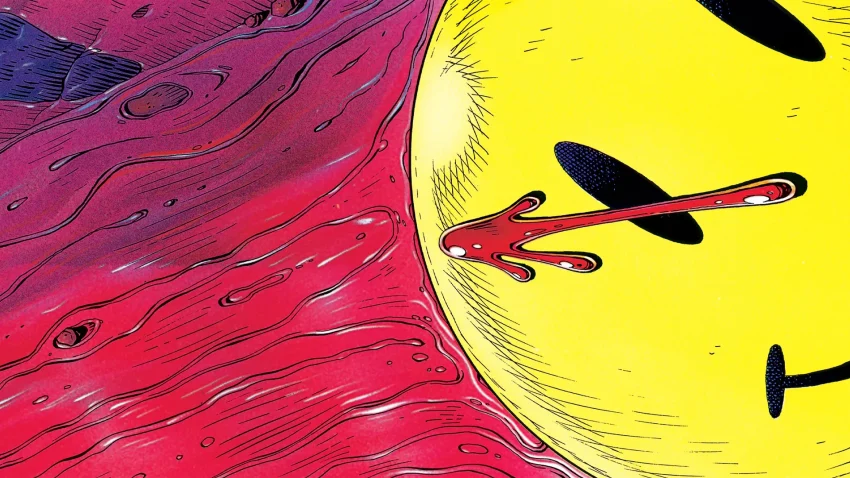

With the Doomsday Clock at 89 seconds to midnight, it’s time to discuss why it feels like Watchmen was written just yesterday instead of 40 years ago.

The 1986 limited series Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons is many things. A pre-apocalyptic epic with a tight, morally ambiguous cast. A modern-day corrective lens for the golden and silver ages of comic books. A targeted deconstruction of the superhero genre. A social commentary on major armed conflicts and the threat of nuclear war…

Here’s what it’s not: light reading. With a tight 9-panel-per-page grid, extensive narration, dialogue, voiceovers, and additional content like in-world newspapers and autobiographies, Watchmen manages to pack in much more information than most comic books. It’ll take you a good long while to get through.

Prospective readers, especially those new to comics, might to balk at the story’s scope and size. You may ask: is Watchmen worth the read in 2025, 40 years after its original publication?

Should You Read Watchmen, and What Is It All About?

Obviously, you should read Watchmen. Especially if you’ve never heard of it. It may not be the most friendly to non-comic-book readers, but it’s the most comprehensive, fully realised graphic novel out there.

As for what it’s about? Many things, including but not limited to:

- The morality (or lack thereof) of power

- The psychology of masked heroes

- Cold War paranoia and the threat of nuclear war

- Surveillance, state control, and moral absolutism

- The chaos of human emotion vs. the cold logic of science

- Whether peace is justified by any means

- Time, memory, and the illusion of free will

Despite an alternate-1980s setting, Watchmen feels timeless—and, in 2025, eerily prophetic.

You don’t need to be a die-hard comic book fan to appreciate it. If you’re into dystopian fiction, political thrillers, philosophical drama, or character-driven storytelling that leaves you unsettled yet enthralled, you’ll find something here. It’s part noir, part sci-fi, part historical alt-fiction, and wholly a literary experience (yes, despite being in the format of the ‘funny pages’).

Watchmen isn’t escapism. It’s a mirror. If you like your fiction with sharp edges and no easy answers—if you’re drawn to stories that unravel society while holding a magnifying glass to the human soul—Watchmen is for you. ‘Nuff said.

Reading Watchmen in 2025 vs 1985 – What’s Changed?

We’ve just hit 40 years since the events shown in Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ 12-issue comic book masterpiece. What’s changed? Allow me to set the scene for you.

1985 — Nuclear Galore

The year is 1985.

The United States and the Soviet Union enter the 38th year of the Cold War, and though disarmament negotiations begin to occur, no one really knows how—or if—it will ever end.

There are more nuclear weapons (nearly 64,000) in this world than there have ever been or ever will be to this day.

It would only take a single day of nuclear war, and only 400 atomic bombs (that’s 0.6% of the total nuclear armoury on Earth) to wipe out humanity entirely.

It is 3 minutes to midnight.

2025 — AIs, Rise Up

Flash forward 40 years to now: 2025, a quarter way through the 21st century.

Artificial Intelligence is a household phrase (even your grandparents know what it is) and every new iPhone comes with an onboard AI pre-installed — with machine learning capabilities that give your phone the ‘ability to learn without explicitly being programmed‘ (has Steve Jobs seen the Terminator?)

Russia, the home of the world’s largest nuclear arsenal, continues to expand its nuclear doctrine and has brought Korean soldiers into its ongoing war with Ukraine, who continue to flout Russia’s threats.

War rages in the Middle East, with tens of thousands of innocent children killed by Israeli military.

It is 89 seconds to midnight.

Both eras feel as though the world is poised on the brink of World War 3. All it would take is the drop of a pin for the clock to hit midnight…

The Doomsday Clock: It’s 89 Seconds to Midnight

It cannot be understated how dangerously close humanity have come to total annihilation in the past century. How closer still we careen along the brink, heedless of warnings, common sense, or even moral decency.

Every day, innocent people die at the hands of those who should protect them. Millions manipulate AI to spread misinformation and sew unrest. The war in Ukraine escalates into its third year, and America, the world’s biggest superpower, sleepwalks right into numerous, entirely preventable, global conflicts.

In the 2025 Doomsday Clock statement, the Science and Security board states that although the clock was only moved forward one second this year, it is the closest we have ever been to total catastrophe.

Every single second forward “should be taken as an indication of extreme danger and an unmistakable warning that every second of delay in reversing course increases the probability of global disaster.”

In 1985, the creators of Watchmen took the Doomsday Clock seriously, and made a seminary graphic novel that serves as a pre-apocalyptic warning. 40 years after its creation, the lesson has not been learned, and things have gotten even worse. Now, all we can do is hope it’s not too late.

The Watchmen Timeline: Pre-Apocalypse Now

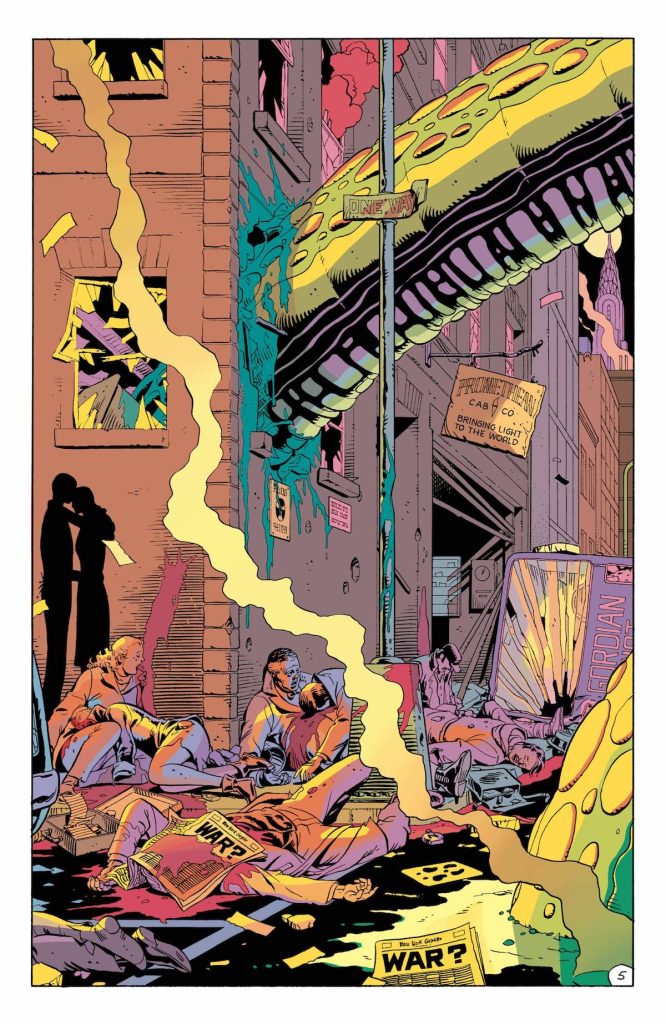

Watchmen does an excellent job capturing the damaged psyche of the morally ambiguous heroes whose tangled lives it weaves its web around. It does an even better job portraying the psyche of pre-apocalyptic society.

Background characters and non-costumed narrators like Dr. Malcolm Long—a psychologist determined to crack Rorschach’s extremist attitude—are all terrified of a seemingly inevitable nuclear war.

Then, We Had Bombs and War. Now… It’s Still Bombs and War

Remember, in 1985, the world was living through a collective nightmare. This prolonged trauma oven had been running for decades, through the Vietnam and Cold Wars, and into this age of nuclear proliferation.

In National Trauma and Collective Memory, Arthur G. Neal—Professor of Sociology—writes that in these periods of prolonged terror (much like the one we live in today, actually), “the central hopes and aspirations of personal lives are temporarily put on hold, replaced by the darkest of fears and anxieties. Symbolically, ordinary time has stopped…”

After all, when Armageddon is inevitable, what purpose does going to work and picking up the groceries serve?

The Ticking Clock Premise Always Works

The overarching metaphor of a ticking clock, a chronic crisis building to a boiling point, is what makes Watchmen’s inclusion of the real-world Doomsday Clock so effective. That’s why it feels as though the seminal graphic novel could have been released just yesterday.

The people of 2025 may be more accustomed to bad news, especially since it is so easy to hear about it (and so difficult not to). But the superabundance of bad news, unfortunately, does not make us more resilient to it.

Instead, unable to escape the daily horror and numb to the anxieties of the 21st century, we begin to disconnect when we should band together.

“Why do we argue? Life’s so fragile, a successful virus clinging to a speck of mud, suspended in endless nothing.”

— Alan Moore, Watchmen

An Alternate (But Not Absurd) Timeline

If you’ve seen or read Marvel’s Civil War, you’d know that while superheroes save lives, they sometimes take them, too—or lead indirectly or directly to death, property destruction, and general chaos. And so, Alan Moore created the Keene Act, a 1977 bill passed to outlaw superheroes—the parent of the Superhuman Registration Act and the Sokovia Accords.

Though any real-world government would be fast to outlaw superheroes, they would be even faster to fold them into their ranks and put them to use as government-approved metahumans.

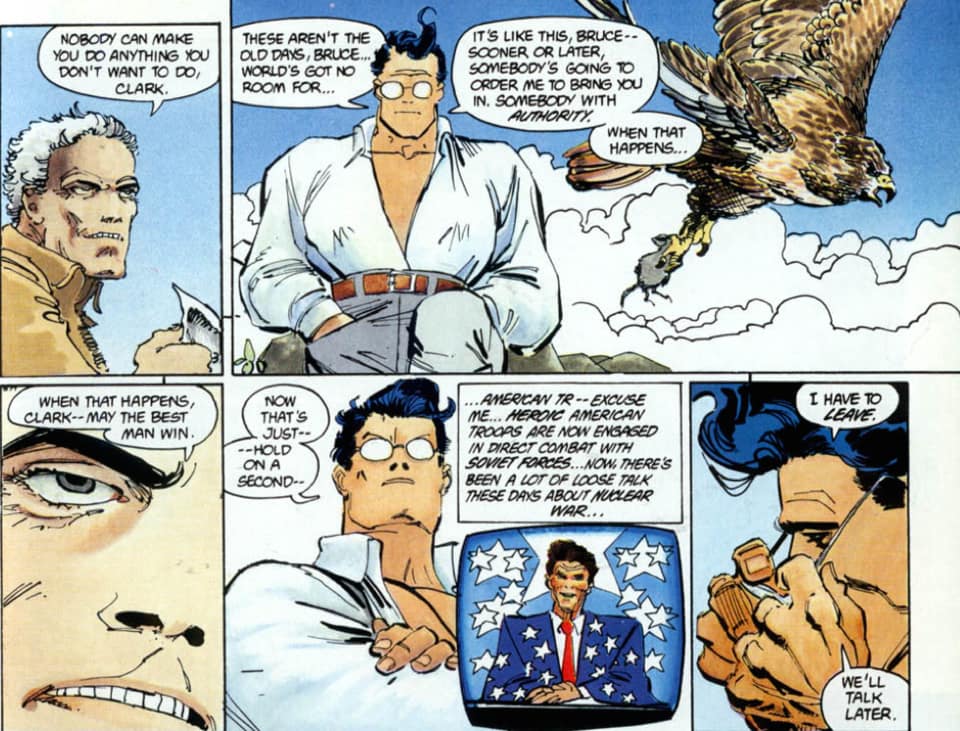

In Watchmen, two key ‘heroes’ continue to operate under the Pentagon, intervening in conflicts like the Vietnam War and—in the case of the god-like figure named Dr. Manhattan—acting as a nuclear deterrent for America’s enemies.

“I never said, ‘The superman exists and he’s American.’ What I said was ‘God exists and he’s American.'”

In The Causes of War, Australian historian Geoffrey Blainey notes that the best (and cheapest) way to win a war is to take away the enemy’s belief that they can win.

Giving Jon Osterman the name ‘Dr. Manhattan’ is a mark of the Pentagon’s boldness. In essence, they give what many in Watchmen call God a name directly linked to one of America’s most powerful cities, then send him to end conflicts such as the Vietnam War.

His almost limitless power is the only thing deterring the Soviet Union at the beginning of Watchmen‘s story. When he later leaves the planet for the solitude of Mars, he leaves the world wide open for nuclear war.

Watchmen Put Both the ‘Graphic’ and the ‘Novel’ Into the Medium

Watchmen was the story that prompted the masses to accept comic books as a serious creative medium.

It was the only comic book to make it onto Time Magazine’s 2005 list of the 100 greatest novels. This feat proved that comics had the potential to craft socially, emotionally, and intellectually resonant narratives. These books, a critic could genuinely declare worthy of the label ‘literature’.

Another Graphic Novel, Released During the Same Year, Had Similar Success

Watchmen’s popularity as a trade collection kickstarted the existence of the ‘graphic novel’ section you’ll find in most major bookstores these days. But one other title can also claim the same. I am, of course, talking about Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns.

It’s eerie noticing, in retrospect, how similar Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns are, in theme and setting. Moore/Gibbons and Miller created them nearly simultaneously with no creative overlap.

Both written in the confines of the pressure-cooker that was the United States circa 1985, here’s what The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen have in common:

- Retired costumed heroes outlawed by their government, pushed into action by civil unrest and the threat of Armageddon.

- A messiah-like figure used as a political pawn (Manhattan and a certain red and blue boy scout).

- A psychological critique of vigilantism and the effect of extreme trauma on the human psyche.

- Strict page layout (9 or 12 panels per page) and the incorporation of in-world news, media, and debates.

“What if Superheroes Were Real?”

What a question. One countless comic-book-related properties have explored since Watchmen’s publication. But it’s a question nearly no titles explored before the 12-issue DC limited series hit stands in 1986. (If you know of one, please let me know in the comments).

Today, superhero ‘realism’—and, by extension, superheroes ‘for grown-ups’—is all the rage. Just look at comics, shows, and films like The Boys, Kick-Ass, Invincible, and even hyper-realistic takes on typically campy heroes like Matt Reeves’ The Batman.

It’s also argued that edgy, hyper-violent, adult takes on superheroes are a direct response to the superhero fatigue plaguing popular culture at large.

Comics Were Always Rooted in Real Life

So what happened? Did comics grow up—or should series like Watchmen fall under the neighbouring umbrella of the graphic novel, while our Spider-Men and Supermen exist purely in funny book land? And where does that leave The Boys and other R-rated tales that don’t quite reach Watchmen’s coveted status?

We’ve been shown time and time again that classic superheroes, while fairly simplistic and one-dimensional upon their initial debuts (some going back to the 1930s), possess the capacity to exist in stories connected to real problems.

Take X-Men: God Loves, Man Kills by Chris Claremont [above left] (in which the mutants tackle religious extremism and televangelism). Or Superman: Grounded by J. Michael Straczynski and Chris Roberson [above right] (in which the big boy in blue takes on abusive parents and suicidal jumpers who question why, with all his power, he couldn’t use his X-ray vision to find the tumor in their partner’s head).

But hold on, I hear you say. Weren’t superheroes created to give us hope? To allow us to escape the mundanity and terrors of the modern industrial world. To tell us ‘things aren’t so bad‘?

Well, yes. But what makes you think that Watchmen doesn’t do that?

‘Inna Final Analysis’ Part 1: The Optimistic Nihilism of Dr. Manhattan

Up until now I’ve been pretty harsh on Watchmen despite praising its literary value, art direction, and complex themes.

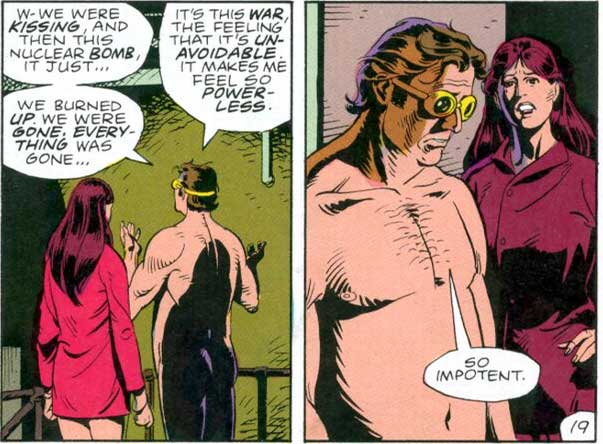

I’ve told you that it portrays its ‘heroes’ as unlikeable sadists, apathetic god-beings, and impotent lowlifes. I’ve told you these heroes aren’t driven by by moral clarity but by trauma, narcissism, and nihilism.

But here’s the thing: Watchmen’s ending reveals a deeper, more human turn.

Each major character’s worldview—Veidt’s utilitarian logic, Rorschach’s unyielding binary, Blake’s fatalistic cynicism, and Manhattan’s cosmic detachment—is eventually undermined by human values. By emotion, memory, and connection.

Watchmen, despite its apocalyptic setting, doesn’t end in despair. It ends in perspective. Allow me to explain. Also, if you haven’t finished the story yet, note that pretty significant spoilers will follow. So, maybe take a reading break before coming back to this part of the article.

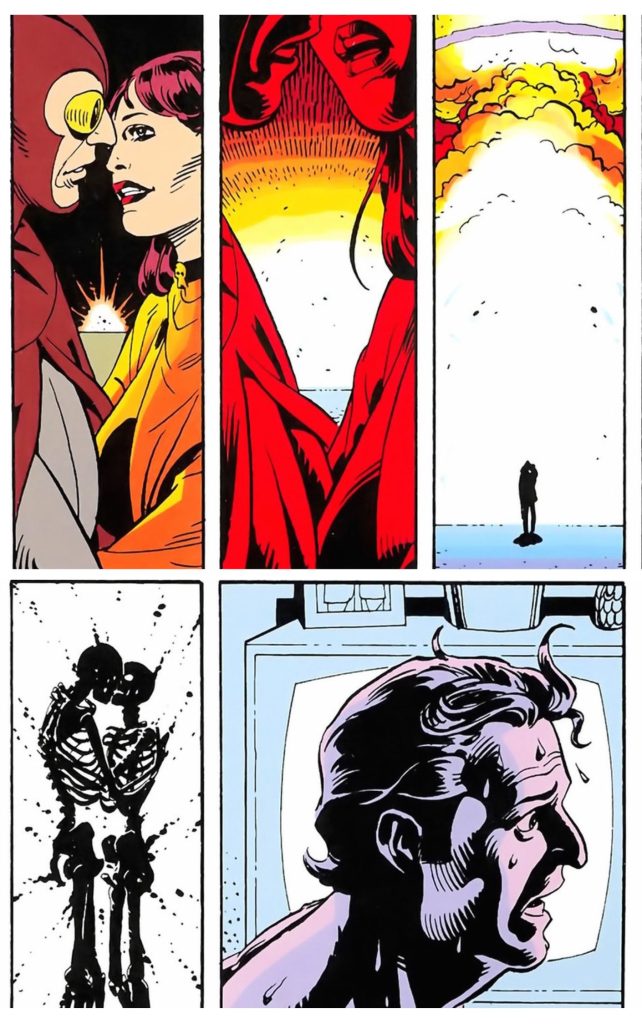

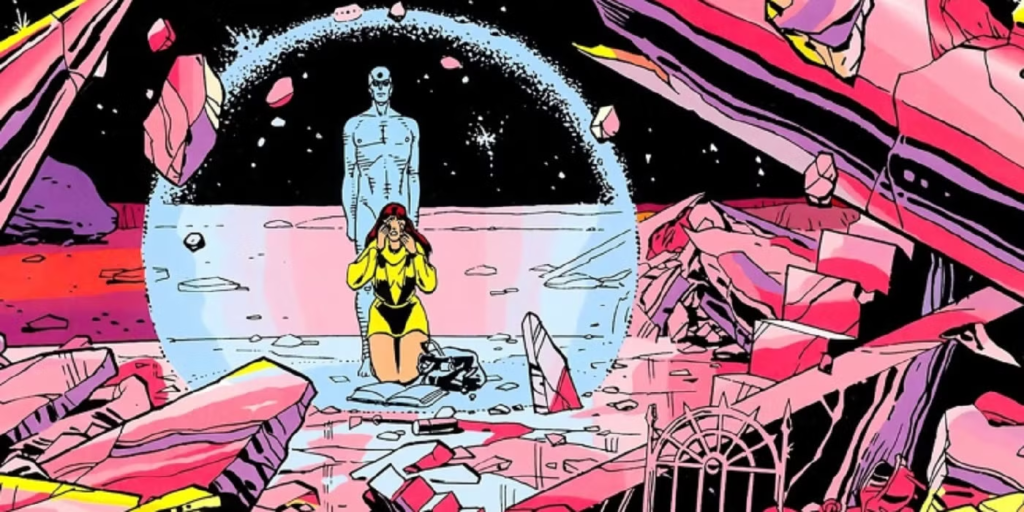

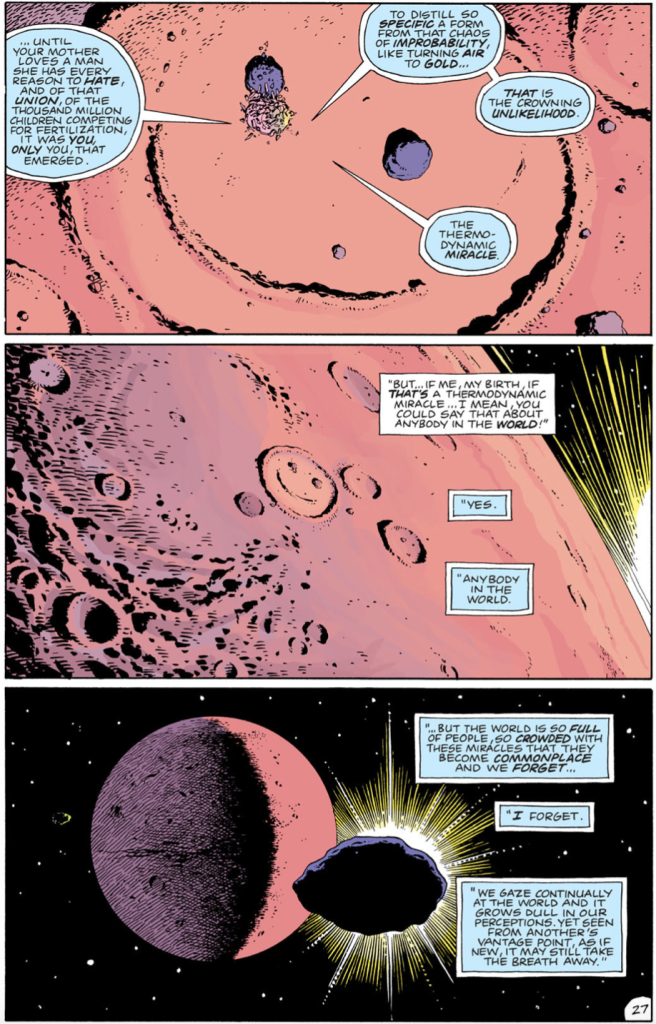

A Revelation on Mars: Laurie’s True Father Is…?

The turning point of the Watchmen narrative comes not through a grand battle, but a quiet revelation on Mars. When Laurie (Silk Spectre) discovers that her father is the violent, nihilistic Comedian, she collapses into despair.

But it’s this very revelation—born of statistical impossibility—that moves Dr. Manhattan to reconsider humanity. Life, he muses, is not meaningless because it’s fleeting, but miraculous precisely because it is.

Manhattan—Jon, he used to be called—spends most of the book drifting further from humanity. To him, time is nonlinear. All things are predetermined. Human affairs are microscopic, barely worth noticing or being part of. But a moment of unexpected clarity, reminds him of the unlikeliness—and therefore the miraculousness—of life itself.

Everything’s a Joke, You Might as Well Laugh, Right?

So, why does Manhattan’s change of heart so much? How does this reframe Watchmen’s ending?

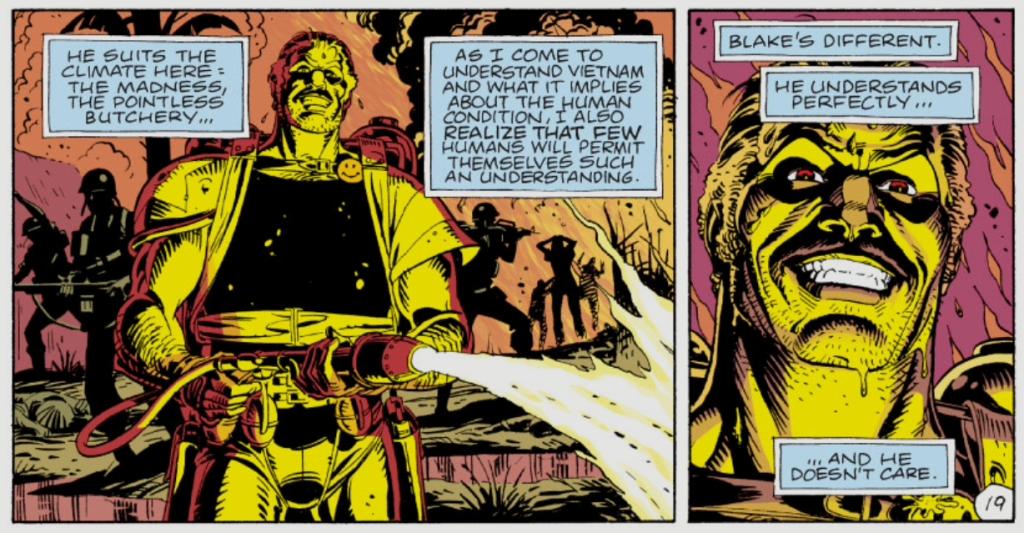

Well, earlier in the story, Dr. Manhattan observes his costumed comrades, such as The Comedian. Edward Blake only appears in flashbacks, since his death is the inciting incident that kicks off the main story.

Manhattan notes that The Comedian doesn’t care one bit for human life. He observes, but does not intervene, as Blake commits countless war crimes with no repercussions.

Blake’s excuse is this: “Once you figure out what a joke everything is, being the Comedian’s the only thing that makes sense”.

The Comedian ascribes to a form of extreme nihilism: the belief that life is meaningless, that society is senseless and so anything you do can be justified because nothing can be justified.

But Dr. Manhattan reassures Laurie (and, by extension, the reader) of one fact. That though the universe is an enormous place filled only with meaningless, the miraculous existence of the tiny and insignificant in such a place is cause for hope. It allows each individual to create their own meaning.

Nihilism, But Make it Optimistic

Faced with the chaos and desolation of the universe, Dr. Manhattan isn’t telling us ‘Nothing matters, so why bother?’ Instead, he tells us, ‘Nothing matters, and that’s why it matters that we still choose to care.’

The sheer improbability of our lives, our choices, our capacity for change, isthe very reason it’s worth something.

This is optimistic nihilism. The belief that in a universe without inherent meaning, we are free—miraculously free—to create meaning ourselves.

Dr. Manhattan could have stayed on Mars, aloof and indifferent. But he returns. Not because he suddenly believes in human morality or logic, but because he sees something improbable and beautiful in human effort.

We love, we fight, we try, despite knowing we’re specks of dust clinging to a rock hurtling through the void.

Manhattan tells Laurie—and, it seems, us, the reader: “Come… dry your eyes, for you are life, rarer than a quark and unpredictable beyond the dreams of Heisenberg; the clay in which the forces that shape all things leave their fingerprints most clearly.”

In a world 89 seconds from midnight, this message hits harder than ever.

Because if a blue god who sees every moment at once can choose to act—to make meaning and human connection—then so can we.

‘Inna Final Analysis’ Part 2: Turning Trauma to Connection

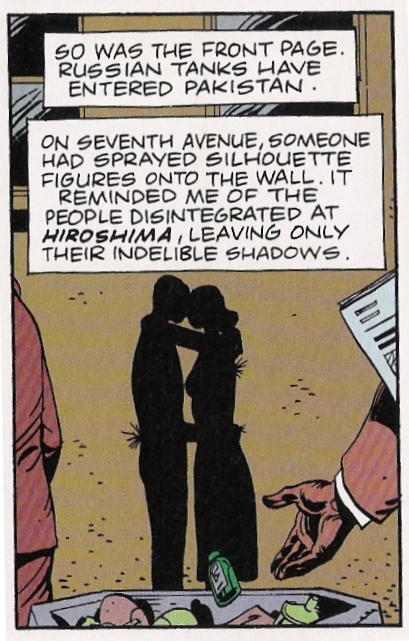

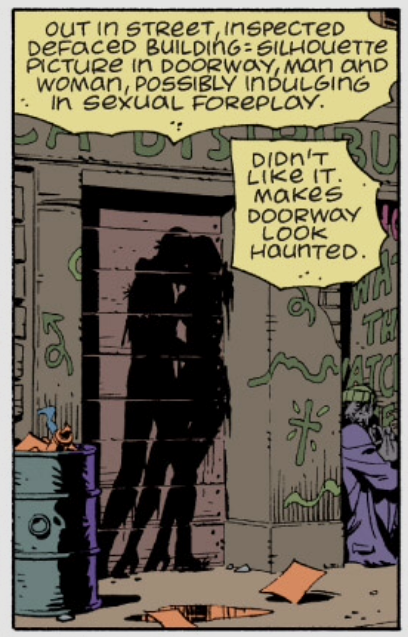

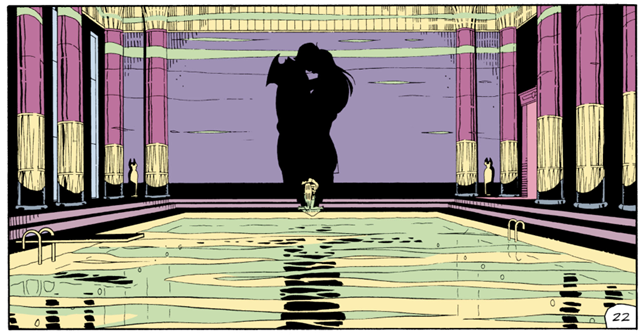

Watchmen’s most quietly powerful motif is the image of two people embracing in silhouette. It’s a recurring image that, over the course of the novel, transforms from a symbol of trauma into one of solidarity.

The Hiroshima Shadows

As I mentioned briefly earlier, Rorschach’s psychiatrist, Dr. Malcolm Long, compares the graffiti to “people disintegrated at Hiroshima, leaving only their indelible shadows on the wall.”

But the silhouette reminds Rorschach of a very different (and formative) memory: the shadow of his mother and one of her clients, burned into his memory.

Now we understand that Rorschach’s unwavering moral code emerges not from abstract conviction but from the emotional fallout of abandonment and isolation.

Even his trademark inkblot mask eventually takes the form of those same embracing figures. The pattern shaped not by fortitude but by longing.

The Civilians in the Margins

Far removed from the antics of the lead characters, several civilian stories have unfolded quietly in the metaphorical margins of Watchmen. The most important centres around two characters who actually share the same name, though we don’t discover that until near the end.

Bernard, a news vendor, begins as a staunch individualist. He lectures the boy reading comics at his stand: “In this world, you shouldn’t rely on help from anybody. In the end, a man stands alone. All alone. Inna final analysis.”

But as the threat of war draws closer, we see him soften. Unnerved by the violence and chaos, Bernard hands Bernie a comic book, then his own hat. “I mean we all gotta look out for each other, don’t we?” he says. “I mean, life’s too short… inna final analysis.”

And, devastatingly, we see that Hiroshima-esque silhouette once again, during the book’s climax. As Adrian Veidt’s psychic blast tears through New York, the explosion preserves one last image at its centre: Bernard and Bernie. Two strangers joined only by proximity and habit, clutching on to each other for comfort in the face of annihilation.

The Brilliance of Reading Watchmen: All the Characters Are Proven Wrong

The 12 issue series rejects nearly all of the main character’s ideologies by its end.

Bernard did not, as he so staunchly claimed, ‘stand alone’. He reached out in his final moment for human connection and comfort.

Rorschach claimed to live a life ‘free from compromise’, yet spent his life wearing a psychological test on his face.

The Comedian insisted that life was a joke and morality meaningless, but died begging for someone to explain the punchline.

Dr. Manhattan likened human lives to those of ants, but spends most of the story reminiscing over his own and others’ experiences and memories.

Yes, the Profane, Gritty, Violent Watchmen is a Story of Human Care

See, the real legacy of Watchmen isn’t just its cynical critique of heroism or even its commentary on global warfare. It’s the reclamation of care and the importance of human connection.

Moore and Gibbons show us that even in a collapsing world, people reach out to find meaning in one another.

In the final pages, we see that Hiroshima silhouette one last time, but this time it’s not tragic, grotesque, or unnerving. It’s comforting.

The textless panel of Laurie and Dan entwined, their shados against the wall, is no accident. It’s an echo of every embrace in the book. A reminder that connection—not power or ideology—is what endures.

It is this ideal that seems even more powerful as we ourselves edge ever closer to Armageddon, 40 years later.

So, Is Watchmen Still Relevant in 2025? And Should I Read It?

In a word? Yes, absolutely. (That was two, I know, but I thought the additive was necessary).

If you’re at all into comic books, speculative fiction, alternate histories, not-so-super superheroes, and social commentary, then Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons made Watchmen for you.

In an era where even superhero films are struggling to distract the masses from the threats of nuclear war, overpopulation, inflation, climate change, and rogue AIs, Watchmen is more relevant than ever. Got superhero fatigue? Read Watchmen. Worried about nuclear war? Read Watchmen.

Look, I know this article has been pretty heavy on the doom and gloom. But it’s worth saying that we still have a chance to turn things around. To renew. To follow the 21st century to its bitter end and come out the other side.

The Doomsday Clock can still turn back—we just need to change our collective perspectives, to remind ourselves and each other how precious life is, how miraculous it is that we can choose to be better.

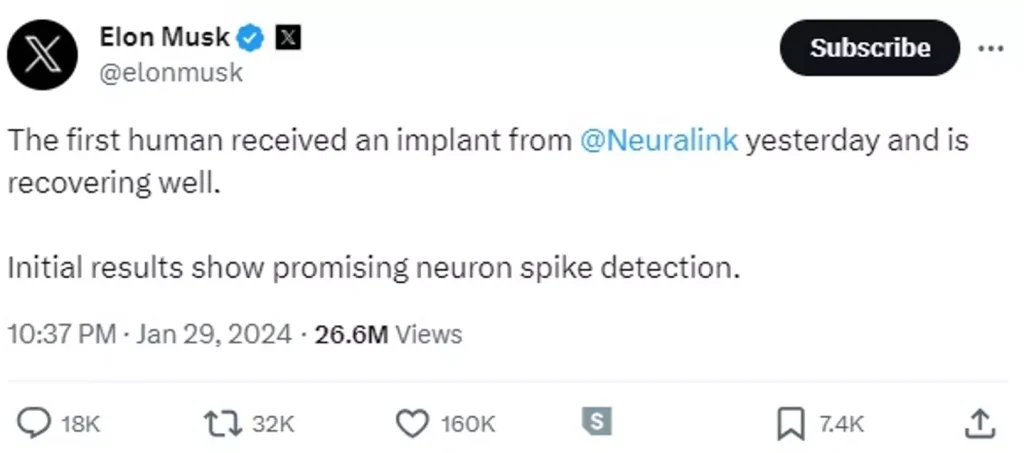

Then again, it’s pretty difficult to take that stance when Elon Musk keeps posting tweets that sound like the in-game texts you find exploring a post-apocalyptic landscape:

Here’s to hoping, I guess.

Enjoyed this post? Why not subscribe to the newsletter, or as I like to say, enlist in the guild? Simply add your name and email and I'll make contact when the next post is ready. Until then, cyberspace adventurer...

Your words move with understated elegance. They are deliberate yet effortless, creating a reading experience that is immersive, contemplative, and quietly transformative.

The text has a subtle musicality, where cadence, rhythm, and phrasing harmonize to create a reflective, immersive reading experience. Each sentence contributes to a meditative flow, engaging the mind and heart, and leaving a lingering resonance in memory and thought.