Yes, superhero fatigue is real. But it isn’t just a pop culture problem—it’s a mirror held up to our times, the canary in our cultural coal mine.

Once, superheroes were our modern myths: archetypes of hope, resilience, and moral clarity. They offered solace and aspiration in uncertain times. We admired them, aspired to be them.

Now we roll our eyes at their latest movie trailers, dissect their CGI and narratives in spoiler-heavy reels, and debate their ethical language in increasingly jaded terms over internet comment sections.

Welcome to life at the turn of the quarter-21st century, where once-classic heroes and tales are plagued by a cultural condition you may know as superhero fatigue—a societal symptom that runs far deeper than oversaturation or sequel-itis.

To dig into this cultural phenomenon, we’ll need to throw comic book history, blockbuster culture, and the state of the world itself under the microscope. Because superhero fatigue isn’t just about supermen. It’s about us, and the cultural exhaustion we’re wading through with our capes half-dragging in the mud.

So, here it is. A somewhat personal exploration of superhero fatigue—not as a fandom gripe, but as a cracked mirror reflecting something sad and broken. And, fingers crossed, something fixable.

What Is Superhero Fatigue? From Blockbusters to Burnout

For the uninitiated, superhero fatigue occurs when you take beloved, iconic characters and churn them through half a dozen reboots, throw billions of dollars at them, and still somehow end up with stories that feel hollow, repetitive, and emotionally exhausted.

It wasn’t always like this—and it still isn’t always like this. But it happens. Superhero fans aren’t on the edge of their seat anymore. They’re like Batman without his trauma: apathetic and uninterested.

Often, superhero fatigue is dismissed as a market dip or creative slump. At worst, it’s wielded smugly like a cudgel against geeks—“Wait, you still like these movies?”

We’re not just seeing the decline of a genre, but a reflection of broader cultural exhaustion, and our complicated relationship to stories that once made us feel powerful, hopeful, or seen.

Today, superheroes are no longer revered. They are feared. With great power comes not responsibility but great narcissism, mental instability, and corruption.

Audiences can no longer suspend their disbelief and instead ask the hard questions about the plausibility of incorruptible paragons of hope such as Superman and Captain America.

But I have some hard questions of my own:

What if the perceived fatigue of superhero-related media is not an issue with the heroes themselves or the projects including them, but a symptom of a larger societal and psychological weariness?

What if we are no longer interested in supposedly timeless heroes due to a disillusionment brought about by our changing relationships with power, identity, and hope—all within an uncertain era of global instability?

What if… we’re the problem?

When Superheroes Were Gods: A Brief History

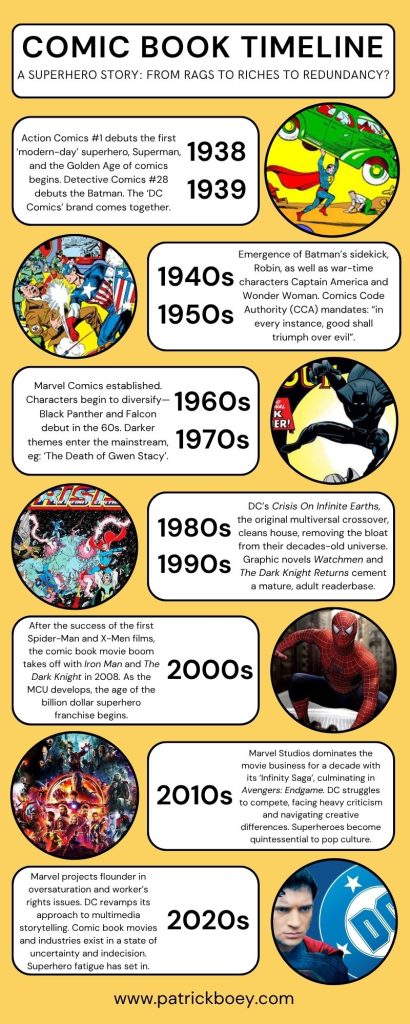

Men and women in tights weren’t always the face of internet memes and stale, billion-dollar franchises. For decades, they were cultural giants, forged in the fires of real-world crises. From Depression-era fantasies to post-9/11 reckonings, the superhero genre has always mirrored the emotional temperature of the times. Let’s trace the rise, fall, rebirth, and fall again of these heroes—alongside the world’s shifting fears and desires. Look, I even made a chart!

Golden Age (1938–1956): Hope in Hard Times

Superman flew into the world in Action Comics #1 (1938), after nearly a decade of the U.S-shattering Great Depression. Co-created by two Jewish immigrants, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, Superman was an indiscriminate life-saver, an immigrant allegory, and a symbol of hope and justice when many had none.

Captain America followed in 1941, punching Hitler on his debut cover months before America entered WWII. Wonder Woman joined the fray in 1941 as well, born of feminist ideals and a belief in peace through strength.

These characters weren’t just entertainment—they were morale boosters, rallying symbols for a nation that needed heroes.

Silver Age (1956–1970): Making Heroes Human

The decades following WWII brought sub-genres of social anxiety, nuclear dread, civil unrest, and space race paranoia. It was the perfect atmosphere for Stan Lee’s deeply flawed characters to shine.

The Marvel Age—and three major titles in particular—changed the lens through which we view superheroes forever.

In 1961, Fantastic Four launched, ushering in flawed, neurotic, deeply human heroes—and the first superhero team that was also a family.

Lee and Ditko’s Spider-Man followed in 1962’s Amazing Fantasy #15, giving the world its first major teenaged superhero (apart from Robin). Peter Parker’s first adventures were filled with money problems, bullying, self-doubt and self-loathing.

Then came the X-Men (1963): outsiders persecuted for their off-kilter appearances and unnatural abilities, results of a genetic mutation they had no control over.

See the trend? Superheroes stopped being perfect paragons, gods among mortals, like Superman and Wonder Woman. They started being us.

Bronze Age to Modern Age (1970s–1990s): Shadows and Shocks

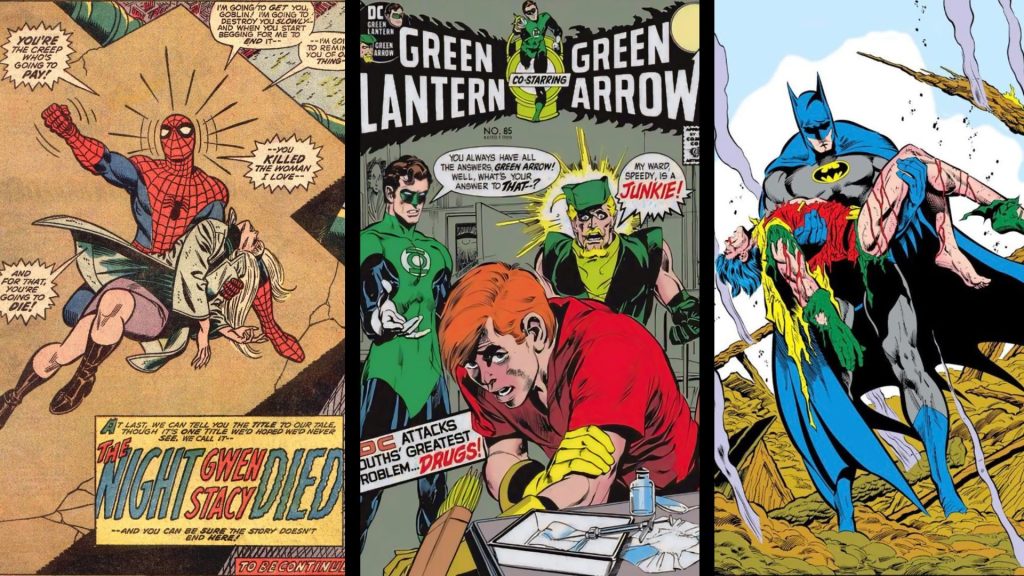

By the 1970s, readers had grown up. So, the genre had to, as well. The Bronze Age tackled drug abuse, racial tension, and social inequality. Comics started getting political, questioning authority and forcing readers interrogate the cost of power. Heroes made mistakes: big ones. Spider-Man’s webs broke Gwen Stacy’s neck. Green Arrow’s sidekick became a heroin addict. The Joker beat a 15 year old to death and escaped Batman’s wrath through political immunity.

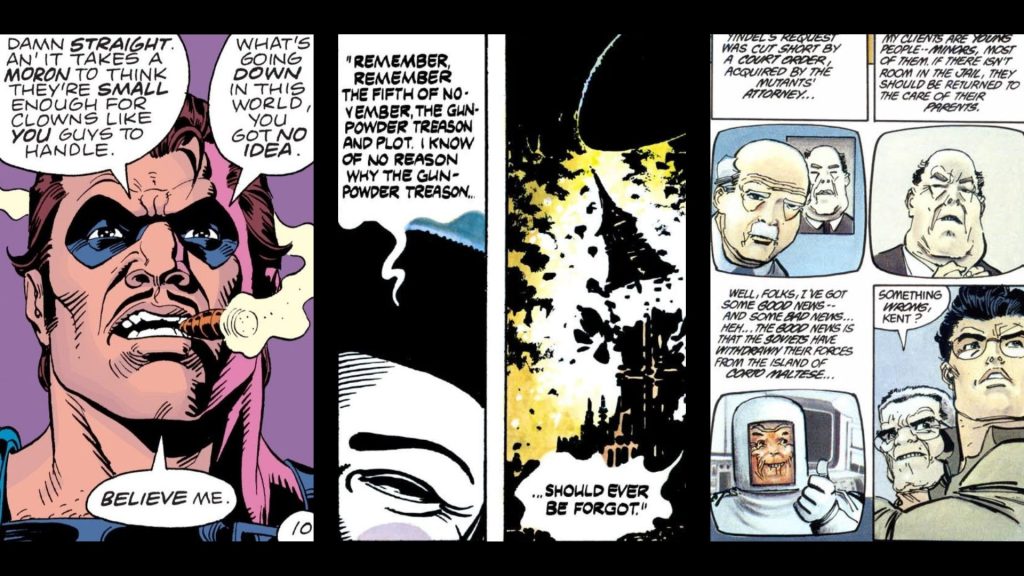

In 1985 and ’86, two seminal works that any comic nerd should know of—Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, and Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns—went all in on deconstructing the entire superhero mythos. Hell, it spun its ethos, pathos, and logos on their heads too. These stories portrayed superheroes as broken, sometimes fascistic figures—reflections of Cold War paranoia, Reagan-era conservatism, and a growing distrust of institutions.

2000s–2020s: The Rise, Reign, and Reckoning of Superhero Cinema

After 9/11, America—and much of the world—searched for catharsis and control. The Sony and Fox-run Spider-Man and X-men films of the early 2000s paved the way for future billion dollar superhero franchises, mixing escapism and fantasy with a healthy dose of realism and social commentary.

Then came the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Starting with Iron Man in 2008 (the same year as the financial crash), the MCU offered a decade-long narrative of triumph, redemption, and intergalactic stakes. It crescendoed with Avengers: Endgame (2019), an event that felt to its fans more like a cultural ritual than a mere movie.

But post-Endgame, something shifted. The real world got darker—climate anxiety, political polarisation, COVID-19, AI panic, economic uncertainty—and superhero stories (across films, shows, even the comics themselves) began to feel oddly disconnected. Once comfort food, they started feeling like fast food: too much, too similar, too soon.

The Culprit of Superhero Fatigue: Comic Book Movies?

There was a time that seeing a superhero film was a rare wonder. When Superman (1978) made audiences believe a man could fly, when Batman (1989) introduced greater media to the icon that DC gets its name from.

Now? Comic book fans could not be more divided. Each new project has as many dissenters as supporters. Each attempt to reinvent the wheel is met with objection and disdain, and each re-use of what is known as the ‘Marvel formula’ is met with cynicism and eye-rolling, if not from critics then from the fans themselves.

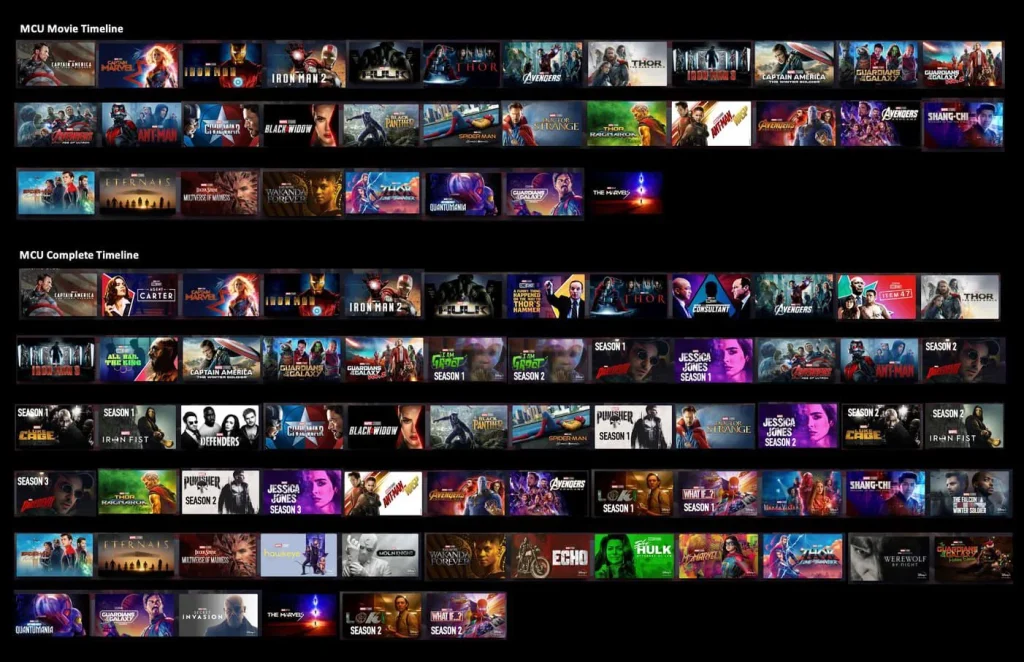

Take the aforementioned MCU, the elephant in too many internet chat rooms. What started as an ambitious cinematic experiment became a content pipeline—seasonal viewing, spreadsheet plotting, AI credits, deepfake resurrections… As viewers, we’re not just consuming stories. We’re not just ‘going to the movies’. We’re navigating release slates, rewatch orders, and lore recaps. The fatigue isn’t genre-specific but systemic. Even Marvel’s most dedicated fans are taking longer and longer to catch up on the expanding catalogue. If this were a comic arc, we’d be entering Crisis on Infinite IPs.

We’re not just ‘going to the movies’. We’re navigating release slates, timelines, and lore recaps. Superhero fatigue has become systemic. If this were a comic arc, we’d be entering Crisis on Infinite IPs.

Studios seem to be scrambling for answers to the lukewarm hero bathwaters: more comedy, more multiverse, more cameos, and why not bring everyone from Harry Styles to Harrison Ford into the fold… But to really solve the conundrum of superhero fatigue, we need to consider the symptoms as byproducts of deeper issues, rooted in cultural psychology, not just storytelling.

Superhero Fatigue: Causes and Symptoms

The further into the 2020s we get, the more superhero fatigue floods out of movie theatre doors and streaming platforms, drenching the comics themselves in weariness. Let’s consider why:

1. Criticism of Repetition, Criticism of Re-invention

We all know the Marvel formula: quippy dialogue, a city-leveling third-act battle, and a post-credit tease for the next instalment—tropes that have bled into non-superhero films (just think about every time you’ve seen a big blue sky beam above a crumbling city, you’ll see what I mean).

Even genuinely ambitious Marvel Studios projects (the heavily criticised Eternals (2021) and Doctor Strange: In The Multiverse of Madness (2022) still had the guts to try something new) buckle under the weight of the Disney template, unable to fully commit to their creative risks, whether due to studio interference or pressure placed on the director from fans.

Genuinely unique and ambitious MCU projects (such as Eternals) still buckle under the weight of the Disney template, unable to fully commit to their creative risks.

On the other side of the fence, the Distinguished Competition faced great adversity for the dark tone and subversise storytelling present in Man of Steel (2013) and Batman vs Superman (2016). Playing catch-up to the MCU, the Zack Snyder-driven DCEU course-corrected; Avengers (2012) director Joss Whedon was brought in to finish Justice League (2017), resulting in an off-putting tonal cocktail of action, comedy, and faux darkness.

The DCEU continued to offer brighter, humorous (and more Marvel-coded) projects like Aquaman (2018), Shazam (2019), The Flash (2023), and Blue Beetle (2023). While these films have their supporters, they’re not exactly superhero classics, either—and they’re plagued by studio interference and multiple actor-related scandals.

Now, Guardians of the Galaxy and Marvel Studios alumni James Gunn helms a company-wide reset. Despite some big creative (and commercial hits), such as The Dark Knight Trilogy (2005-2012), Joker (2019), and The Batman (2022), DC’s credibility has been eroded by its disjointed, uncertain release slate, and it’s up for debate whether audiences are ready to trust again.

Marvel Studios, love or hate them, have a brand identity. But until Superman (2025), nobody really knew what to think of DC’s image. It may be too early to tell, but Gunn’s Superman may herald a new age of superhero films.

2. Franchisitis – When Fandom Becomes Homework

To put it bluntly, keeping up with every new show, movie, and crossover can quickly become exhausting, especially when they all fall under the umbrella of a single Mickey Mouse-ified universe. You’re expected to have seen five prior movies, two spin-off shows, and a mid-season streaming special just to understand who’s on the other end of a phone call, or standing in the distant background.

Casual viewers who want a breezy watch after a hard week at work don’t want to put in that kind of work, and even die-hard fans aren’t showing up for premiers and season finales anymore.

3. Exit Thanos, Enter Employee Disatisfaction and Cancel Culture

Superhero movies are synonymous with big, CGI fight scenes and spectacle. However, due to the huge amounts of work that go into computer generated imagery, engineers and artists face near insurmountable time crunches, resulting in rising discontent among graphic artists, particularly those in Marvel and Disney’s employ.

Considerable numbers of VFX artists sought to unionise and boycott the studios over the working conditions. This comes in line with criticisms of the decline in CGI quality overall, leaving no doubt about the reasons why.

Then there’s the numerous actor-related scandals, combining with the way cancel culture leaks into every facet of public perception, pressuring major studios to cut ties with actors portraying key roles in their universes. A minor character? No big deal. But the next big bad to rival Thanos, who you’ve named a whole movie after, who’s meant to bring the Avengers to their knees? Bit of a problem.

4. Oversaturation, Duh!

To get through all the content modern Marvel has to offer, you would need 8,807 minutes (6 days) of viewing time, and that’s not including films produced by other studios such as the X-Men, Spider-Man, Blade, Hulk, and Fantastic Four movies, to name a few. So, depending on who shows up in Avengers: Doomsday (2026), the amount of time you need to catch up on the entire MCU’s storyline could skyrocket even further.

Since, due to multiversal shenanigans, most of these timelines are confirmed to take place inside the MCU multiverse, the complete MCU viewing time just got a lot longer.

Look: the vast amount of superhero content is not necessarily, in itself, a bad thing. After all, comic book fans have decades of ongoing series, limited editions, and crossovers—that just means there’s more to read, more to collect, more to choose from. After all, you’d be hard-pressed to find a comic book reader who has read every single issue of DC comics. They choose their favourite characters, writers, and artists, and go from there.

Maybe that’s what needs to change. Instead of there being a cultural obligation to catch every MCU instalment, fans should feel free to pick and choose their own entertainment—and the creators should allow for this.

If audiences don’t feel like seeing a particular movie, they could just, well, not see that movie. But then again, Marvel fans are a curious breed. We don’t want to miss the chance that that character could appear in a post-credit scene, or get confused about why Loki’s still alive in Avenger’s: Doomsday, or why the original X-Men from the 2000s films are there, too.

Losing Spider-Man: The Personal Fallout

Quick pause on the hate train to explain why I’m really writing this article (if you just want to get to the part where I start solving superhero fatigue, skip to the next header).

It was a Tuesday night, mid-pandemic haze, when I found myself watching Spider-Man: No Way Home for the second time. I wasn’t sure if it would hold up the same way it did in theatres. I braced myself for the nostalgia overload, the multiverse gimmicks, the corporate chessboard moves designed to placate the old guard.

And to be fair, it worked. For a while—it’s a fun movie, after all; it gives us some of the most visually thrilling Spider-Man action in all of Tom Holland’s MCU screen time, and Willem Dafoe clearly revels in playing an even more villainous Green Goblin.

But after the credits rolled, I didn’t feel awed or overjoyed, not even at seeing my childhood heroes back from their Sony-induced exile. I felt oddly dejected. Maybe it was the fact that having these classic villains show up to fight an alternate Spider-Man who’d never met them before felt cheap and unearned, a gimmick to win back fans of the older movies. Maybe it raised more concerns than solutions about the future of Spider-Man in cinemas.

Whatever it was, I started fast-forwarding through some Marvel-Disney shows I hadn’t caught up on, just to stay in the loop, or perhaps to reinvigorate my love for the genre, but I could barely finish them. The excitement had vanished. I didn’t realise it yet, but I was in the early stages of superhero fatigue. And not even Spider-Man could cure me.

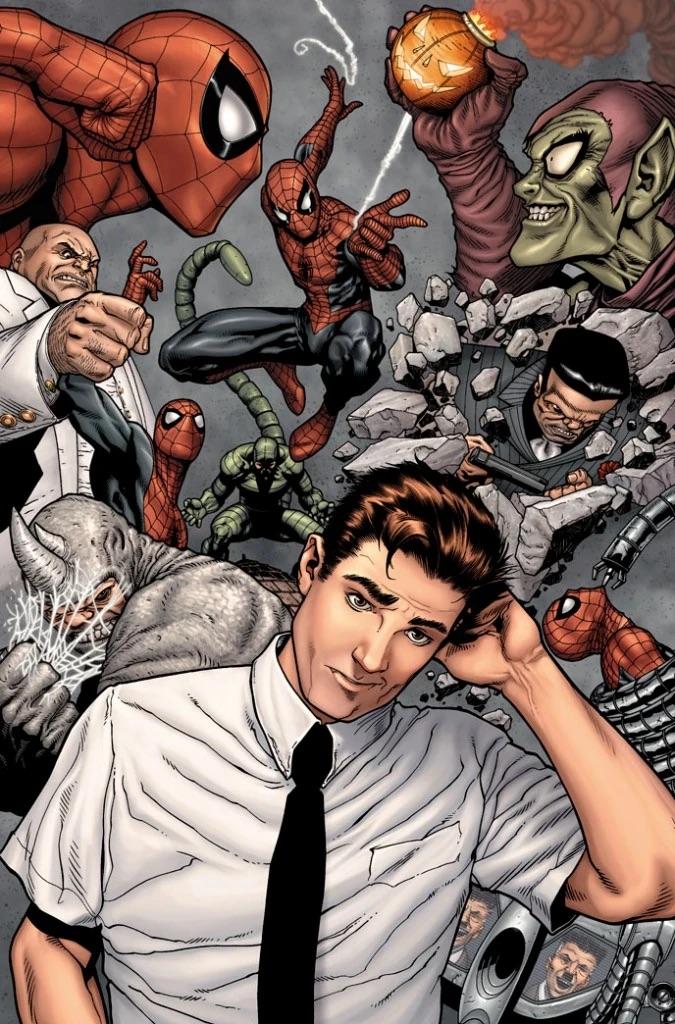

Look, I’m a Spider-Man person. Full stop. I’ve read thousands of issues bearing the name Spider-Man in one form or another. Amazing, Spectacular, Ultimate, Symbiote, Web of, Miles Morales, Spider-Gwen, Noir, Symbiote, 2099, even Spider-Ham. I was the kid who got in trouble for etching Spider-symbols into my homework. My shelves are stacked with omnibuses and boxes of back issues like sacred texts.

So when I say this, it comes from a place of near-lifelong loyalty: I’m not sure if I relate to Spider-Man anymore, at least not in the way I once did. And maybe… I’m not supposed to.

See, Peter Parker was always sold to us as “the Everyman”—awkward, broke, selfless, burdened by responsibility.

But in recent years, the more I read Spider-Man—old or new—the less the Everyman label feels real.

It’s not just that, in my early-mid 20s, I’m beyond the age most merchandisers consider appropriate for a Spidey fan.

It’s not even because of the recent MCU-entrenched, Iron Man-worshipping Tom Holland films, or Sony’s relentless IP mining, butchering Spider-Man’s villains and supporting cast in poorly written spin-off films, sans Spider-Man.

It’s the sense that, somewhere along the way, Spider-Man stopped evolving.

The character’s been stretched so thin, across so many mediums, timelines, and suits, he’s become less of a character and more of a commodity.

Editorial decisions in the comics haven’t helped. The infamous “One More Day” storyline, in which Peter’s marriage to MJ was erased from continuity via a deal with Mephisto, felt like a betrayal—a literal devil’s bargain to preserve a brand image rather than grow a character.

More recently, flagship title The Amazing Spider-Man (TASM) has lurched through retcons, shock deaths, and continuity resets that seem more interested in triggering online discourse than telling meaningful stories. At some point, Spider-Man stopped swinging forward, and just kind of did loop-de-loops around a flagpole, or something.

At some point, Spider-Man stopped swinging forward, and just kind of did loop-de-loops around a flagpole, or something.

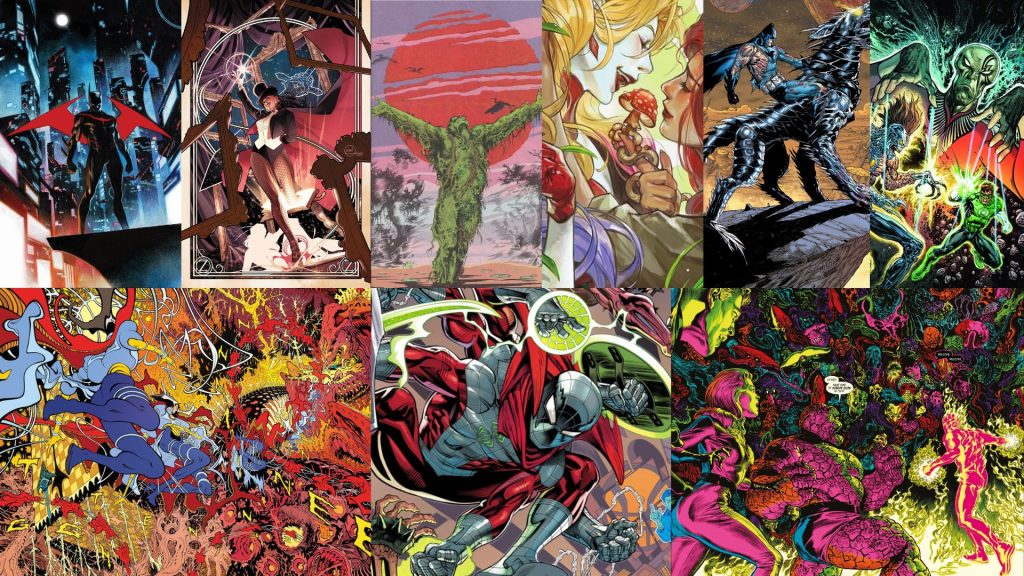

And yet, I still love what the character represents. Maybe I always will. I just don’t look to him for answers, anymore. I look to other stories—stranger ones, darker ones, more uncertain ones. Sandman, Swamp Thing, Spawn. Those aren’t superhero stories, by the way. They’re meditations on identity, mortality, mythology, and madness. I don’t relate to them—but I find them true in a way that’s satisfying to me. They don’t ask me to see myself in the hero, but to lose myself in the questions they raise.

All that to say… sometimes, we outgrow what we love—not because they fail us, but because we need different answers, answers that they can’t give us anymore.

Superhero Fatigue is Cultural Burnout in Disguise

Unfortunately, this whole superhero fatigue debate isn’t just about Spider-Man. Or Marvel. Or cinematic universes.

Superhero fatigue is a symptom of something deeper: a burnout that’s been festering for years, and is now erupting into every genre, every timeline, every multiverse. We’re tired not just of capes and catchphrases—we’re tired of the world they reflect, and the illusions they can no longer sustain.

The phenomenon of superhero fatigue signifies more than an oversaturated market and exploitation of popular IPs. It stems from a cynicism that mirrors the paranoia and disassociation infesting the delicate, near-infinite web our society has built over the past century, across the Earth and through cyberspace.

Whether you focus on the hate comments, smear campaigns, or boycotts, there’s no getting around the fact that some comic book fans have generated a bad name. But it wasn’t always like this.

Let’s see why a quarter through the 21st century, superheroes are tearing us apart rather than bringing us together (insert relevant Tommy Wiseau GIF here).

1. Psychological & Social Change

We live in a world of near-constant crisis. Climate catastrophe, political unrest, war, economic collapse, pandemics—they aren’t abstract background events, no matter how much we want to pretend they are. They’ve become our baseline. Superhero stories once offered a release valve for this pressure, a fantasy of control and justice in a chaotic world. Now, they often mirror that chaos back at us.

Superhero satire, employed to shocking effect in shows like The Boys, channels our cultural despair into dystopian narratives where institutions are corrupt, heroes are complicit, and hope is a marketing slogan. There’s power in that realism—but it’s also exhausting, and frankly pretty depressing.

2. The Post-Trust Culture: Paranoia and Loss of Innocence

Once aspirational figures, superheroes are now cautionary tales. Homelander and Omni-Man aren’t anomalies—they’re archetypes. They represent a collective fear: what if our protectors are our oppressors? What if the people we trust most are the ones manipulating us? What if they don’t really care if we live or die?

This shift reflects a broader post-trust culture. Institutions—government, media, science, religion—have all faced massive public skepticism, if not outright collapse. In that environment, the superhero as saviour rings hollow. It’s no wonder that many recent heroes are loners, outcasts, or downright antiheroic.

The ensemble casts of today don’t form Justice Leagues—they form support groups. The age of Superman’s smiling morality has given way to Peacemaker’s bloodstained redemption arc, to the Suicide Squad’s anarchical glee, to Deadpool’s meta-critical commentary.

Peacemaker, Venom, Dr. Manhattan, Omni-Man, Homelander, and Deadpool – none of these comic book characters or their film/animation counterparts are considered heroic by the usual definitions. Some are more villainous and deranged, others apathetic or morally selective. Yet the popularity of antiheroes and cynical, post-trust portrayals of metahumans has grown exponentially on this side of the 21st century.

3. Desensitisation and Dopamine Burnout

I remember being a kid, wanting nothing more than to get my hands on an iPod touch (anyone remember those?) just so I could browse Instagram, watch Youtube, play mobile games. Now, I want nothing more than to able to do without my phone. To go into the movies surprised, not spoiled by fan theories and deepfakes and set leaks. To not hear the same TikTok audio a dozen times in one doomscroll session.

Superhero media has become a mirror of our wider attention economy—loud, endless, and hyper-connected. It’s a cultural pattern rooted in how we’ve learned to consume information. TikTok, Instagram Reels, YouTube Shorts—these platforms are engineered to spike our dopamine with each swipe.

This kind of hyper-intermittent feedback loop triggers the same reward centres as addictive substances, rewiring our attention spans and numbing our emotional responsiveness. We’re training our brains to crave novelty over depth, spectacle over story.

And this overstimulation bleeds into how we engage with superheroes. We expect instant payoff. We get bored in moments of quiet. We lose patience for anything that dares to build slowly or sit in discomfort. Even epic showdowns feel flat now—not because they’re poorly executed, but because our capacity to feel awe has been dulled by constant hits of micro-entertainment.

We’re not tired because the stories are small. We’re tired because the noise never stops.

4. Lack of Collective Optimism

Superheroes are fundamentally about belief: in goodness, in redemption, in the power of one person to change the world. But right now, the world feels too big and too broken for that. In an age of war, ecological collapse, mass protests, and economic precariousness, the idea of a single person saving the day can feel not just quaint—but insulting.

James Gunn’s Superman addresses this matter: this iteration of Superman does not care one bit for technicalities, borders, and trade wars. He cares about saving lives, and that makes a lot of people in Metropolis (and on our real-world interwebs) very upset.

Superman (2025) addresses how the very archetype of ‘The Superman’ can function and remain relevant in a world so overrun by chaos, political warfare, and military agendas. Depending on the execution, this could be a big step forward for superhero movies, as the content may reflect or mirror current affairs affecting society’s perception of authority.

How to Cure Superhero Fatigue: A Cultural Prescription

Superheroes, at their best, are myths. And myths can evolve. They can be queer, disabled, diasporic, neurodivergent, Indigenous. They can explore horror, romance, satire, family drama, magical realism. What they can’t be anymore is one-size-fits-all.

To their credit, studios are starting to pick up what we’re putting down, taking noticeable steps to remedy their the fatigue of their audiences. Marvel Studios’ recent move to reduce their annual output is a good sign, and has already resulted in tighter, more unique instalments like Thunderbolts* (or The New Avengers, I guess?)

DC, meanwhile, has undergone a dramatic creative reorganisation, promising a new era under James Gunn’s leadership that might finally let its characters breathe again, and let comic book movies feel like comic books rather than copy-paste action flicks.

But studio pivots alone won’t solve society’s deeper fatigue. If superhero fatigue is a symptom of cultural burnout, then what we need isn’t just tighter editing or fewer spin-offs—we need new forms of storytelling (or old ones reimagined) that can surprise us, nourish us, challenge us.

So, here are some carefully considered prescriptions from a lifelong fan. They’re not mandates. They’re suggestions, and they are offered with love. (Marvel, don’t hate me. DC, call me.)

1. Diversity of Structure and Storytelling

Let me be clear: I don’t mean every film has to have a different director or that there needs to be a dozen plot twists and red herrings. All I’m asking is that we allow films to surprise us again: not with cameos, but with tone, pace, theme, setting, and plot.

As much as I enjoyed Thunderbolts*, for example, from the moment *spoilers* Bob went all ‘dark mode’, I already knew we were hurtling toward a redemptive group hug and a power-of-friendship climax. What I think would’ve been really interesting, however, is if we’d spent more time in the void with each member of the team. This would’ve allowed the film to dive deeper into its psychological core, allowing each character to confront their guilt, grief, and rage. And, it would have allowed the cinematography to shine. Imagine the layers of the darkness peeling back through the lives of their characters like torn paper as they battle fragments of their pasts. That way, you get your surprise appearances and setting changes while still offering a compelling story.

2. Character Studies: Deeper, Not Bigger

When all else fails, break a superhero down to the barest bones (or, I guess, strip the costume down to its emotional seams).

Take 2017’s Logan, which was meant to be Hugh Jackman’s final send off as the titular character before Ryan Reynolds enticed him back into the fold using a “big bag of Marvel cash” for 2023’s Deadpool and Wolverine. Despite not having much of the usual superhero cinema language, the Wolverine-led dystopian western was a powerful film because it was honest about mortality, legacy, and regret. It felt like the actual end of something. It treated Wolverine not as an action figure, but as a man who had outlived his mythology and had nothing left to live for. That’s mortality. That’s human.

Give us character arcs, not content calendars. Let the gods be fragile. Let them bleed, and weep, and yes, let them die, and rest in peace.

3. Bring On The Eye Candy

One of the most visually disheartening trends in the superhero genre has been the creeping realism of its production design. Grey skylines, sterile labs, military bases, smartphones, Zoom calls—do we really need our superheroes to live in the same flat world we’re trying to escape?

Take the mostly flat visual language of, say, the Captain America films, and contrast them with the animated Spider-Verse films—kinetic, layered, bursting with visual metaphor and comic book iconography. Or X-Men ’97, which manages to preserve the emotional resonance of the original series while pushing its style into something sharp and contemporary. Even What If…?, when it dares to get weird, demonstrates how animation can free superhero narratives from the limits of budget and actors or even plausibility.

But it’s not just about style for style’s sake. Visual innovation communicates tone, theme, and imagination. It gives the audience permission to re-engage. We don’t need bigger name actors or bigger green screens: we need better art direction and commitment to comic’s visual language.

4. Elseworlds and Status Quo Changes

The connected universe model was once groundbreaking. But we’re now in the aftershock of that revolution. Serialisation has become a burden, not a benefit—a blessing turned bureaucracy.

That’s why films like Joker and The Batman, which take an ‘Elseworlds’ approach to storytelling, have struck the right nerves. They’re contained in a creative bubble, leaving directors free to take risks and tell a story untethered to a larger universe. These stories can still exist as a separate universe in a shared multiverse, but don’t require viewing 36 films and 29 shows to understand. They exist in their own tonal pocket, like graphic novels on a different shelf of the same library.

Studios are catching on. James Gunn’s DC reboot will include “Elseworlds” projects running alongside its main continuity. That’s a smart move. But I say go further. Go mythic. Go off-planet. Let creatives take the toys out of the box and play.

The DC and Marvel comic book universes are so rich with history and variation that it would be a shame to only focus on the here and now. We’ve seen dark, gritty, and grounded Gotham, seen it to death. How about epic mythological adventure? How about a cyberpunk, neo-noir Batman Beyond film? How about Zatanna: In Reverse, a mystical adventure that plays by the rules of Tenet? Or Swamp Thing/Poison Ivy: Going Green, in which we dive into the DC universe’s cosmic plant force and maybe go to war with Earthly (and otherworldly) polluting corporations? The possibilities are endless, and they’re all there in the comics. Let’s bring them to life, why don’t we?

If I was a board member or creative director at Marvel or DC studios, instead of a penniless freelance writer and artist, then my main note would be: the multiverse shouldn’t just be a plot device—it should be a creative license. It should be permission to explore the wacky, wondrous world of comic books, and surprise us with the discoveries bound to be made.

Final Thoughts: The Hero Still Has a Place

Superhero films and comics are at the brink of a new era. Once the gold standard, Marvel’s recent projects have been more hit than miss. Comics are starting to innovate in unexpected, modern ways. DC is powering through it’s new strategy. Hope is on the horizon. Let’s stick with it and see where it leads.

Audiences haven’t turned against superheroes—they’ve become disillusioned by the systems behind them, both in fiction and reality, which has resulted in superhero fatigue.

But superhero burnout isn’t a death knell for comic books or superhero media. At its simplest, the issue is a misalignment between audience expectations and industry offerings.

It’s been nearly 90 years since Superman’s birth in the Great Depression. In the post-pandemic, pre-apocalyptic landscape of the 2020s, it feels organic for there to be a cultural reset—in fact, it seems only necessary. Superhero fiction is adaptive, mythic, and capable of metamorphosis, much like the Greek gods of yore, or a certain Baker Street Detective.

Right now, it’s clear that the way superhero stories are told needs to change—and it’s happening. There are exciting things happening in DC and Marvel comics, such as their new Ultimate and Absolute imprints (I highly recommend Absolute Batman, Ultimate Spider-Man, and Absolute Martian Manhunter as key innovative works).

It seems like the folks over at Hollywood are aware of the trends, too, and are making moves to realign their creative direction with the cravings of their audience.

DC’s ‘Absolute’ and Marvel’s ‘Ultimate’ imprints have seen some of the most drastic and well-received reinterpretations of classic comic book characters in decades. Characters like Martian Manhunter, Green Lantern, Black Panther, and more receive revamps with unique art and writing styles. Time will tell if these iterations of the characters will endure in comic book history.

To put a (very) long story short: the world is tired, angry, fractured—but we still need stories of people who try. We don’t hate superheroes—we’re asking more from them.

We’re looking for someone to carry the weight bearing down on our shoulders. To lift us from the darkness of lockdowns, internet forums, and 9-5 grinds. But we can’t forget that we have a role to play, too. To slow down and smell the roses. To ask the right questions of ourselves and our heroes.

As for me? I want to feel good about seeing Spider-Man swinging off to save the world again—not because it can be saved, but because he believes it can be saved. That’s not too much to ask… is it?

Enjoyed this post? Why not subscribe to the newsletter, or as I like to say, enlist in the guild? Simply add your name and email and I'll make contact when the next post is ready. Until then, cyberspace adventurer...

This made me think of how even our heroes have become too complex or compromised to offer escapism. Maybe we’re craving stories that help us feel more grounded rather than larger-than-life.

Exactly. We need to be reminded that we’re human, too. Post-Superman, it’s even truer, and I’m glad people are starting to see this.

I was curious if you ever thought of changing the layout of your blog?

Its very well written; I love what youve got to say. But maybe you could a little more in the way of

content so people coould connect witth it better. Youve got an awful lot of text for only having one or two pictures.

Maybe youu could space it out better?

Hi there, thanks for the feedback, I’m glad you like the writing. If you don’t mind me asking, what do you mean by more in the way of content? Would more pictures, infographics, audio/video elements help with the engagement? Maybe cut down the word count for a quicker read? Would appreciate your insight.

Best regards,

Patrick