By the time we’re treated to a clan of vampires step-dancing to ‘The Rocky Road to Dublin’, you already know that Sinners is a musical, but not the usual kind. Nor is it your average bloodsucker flick.

In Sinners (2025)—the horror musical everyone’s talking about—hit-for-hit director Ryan Coogler trades Wakandan vibranium for bloody fangs and turns the gothic into gospel. What begins as a slow-burning Depression-era drama unspools into a genre-blending fever dream where vampires step-dance to Irish jigs and the veil of life and death is shattered by the sheer awesomeness of blues music.

If you had to ask me what makes Sinners such a beautiful breath of unholy air, it’s that it poses a question that isn’t as heavily explored in popular culture as it rightly should be: ‘What if music wasn’t just emotional or performative—but inherently supernatural? What if the right musician with the right performance was capable of using their natural gifts to reckon with history, resurrect memory, and unmask evil?’

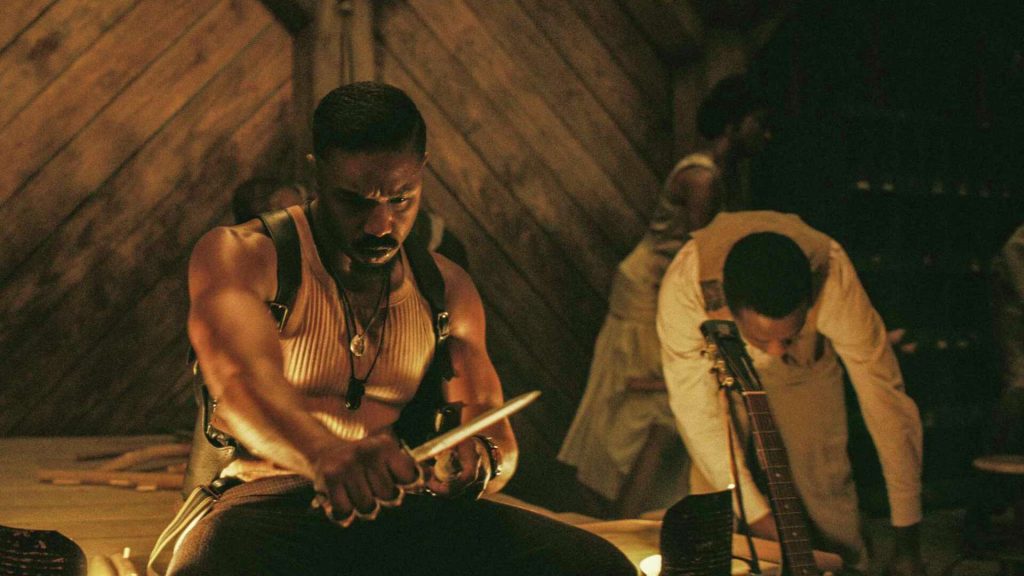

Anchored by Michael B. Jordan’s dual roles as twins Smoke and Stack, and newcomer Miles Caton’s performance as Sammie “Preacher Boy” Moore, the rapturous, boundary-pushing score from Coogler’s frequent collaborator Ludwig Göransson pushes Sinners across the lines between sincerity and spectacle, haunted and hopeful.

I’m sure that if you’re searching for answers on the twists, turns, and tunes of Sinners and found this article, then you’ve discovered that much has already been said about the film’s aesthetic wildness and tonal audacity. But after my initial watch and a frantic Google search in the cinema bathroom, I decided I needed to push a little deeper as to how this particular flick has managed to hit all the right notes with all the right people.

In this article, we’ll unpack how Sinners uses musical traditions to critique cultural appropriation, reframe horror tropes, and make an argument about who controls narrative—and who gets to raise the dead. Heavy spoilers ahead, lads and lassies..

‘That’ Scene Transforms Sinners From Period Drama to Supernatural Musical

While ‘Sinners’, in its entirety, is certainly a diegetic musical, it isn’t till the midway point when the musical blends with the mystical to create something truly unique. Until then, it’s a pretty straightforward family drama with a little bit of travellin’ blues here and there.

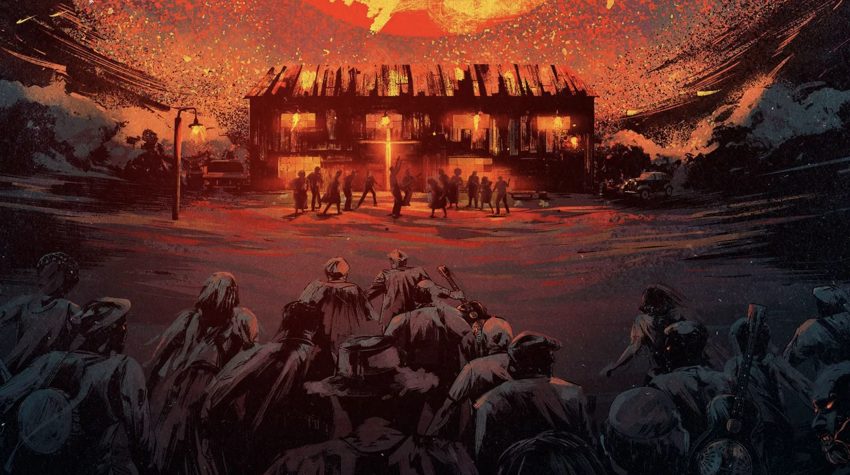

But then—in an unforgettable, hypnotic sequence in which Sammie’s musical prowess quite literally sets the roof on fire / shreds the joint / brings the house down / whatever lingo you want to use to describe it—the audience is treated to a mesmerising and hypnotic genre mash-up that scores the film’s pivotal moment.

If you were lucky enough to go into this film completely unspoiled, you probably had the same reaction as I did. Something along the lines of: ‘This is a fantastic song. Oh, we’re getting a fade-out now. I suppose we’re about to see the true power of blues music—is that an electric guitar? Is that Jimi-freaking-Hendrix??’

Yup. A Hendrix lookalike, plucking a killer blues-driven rock solo, literally steps into frame from out of the future to join the performers on stage. This ghostly guitarist is the first of many figures you’ll see playing and dancing in this impressively ethereal scene, which was filmed in three separate IMAX powered takes, stitched together to appear continuous.

‘I Lied To You’, sung by real-life blues singer Miles Canton in his debut acting performance, begins as a traditional blues tune, complete with untuned piano, twangy guitar, church-boot stomps, and crooning baritone. It’s a fantastic performance whose opening verse remains firmly rooted in the first half of the film’s identity as a 1930’s period piece. Pretty straightforward, right?

It then becomes clear to the audience what the narration in the opening sequence of the film meant, and it’s exactly what it says: that Sammie ‘Preacher Boy’ Moore has the ability to create and perform music so powerful it breaks down the boundaries of time, summoning spirits of past and future, and forces of evil from beyond the veil, namely a trio of vampires, who, by the way, are much more than the ‘white devils’ they appear to be. But more on them later.

Musical Eras & Styles in Sammie’s Big Juke Joint Show

The more apparitions from past and future that arrive in the slowly burning-down juke joint, the more the Delta blues song mashes up with hip-hop, rock, tribal, and other African-American musical styles. To touch upon the massive breadth of this set-piece’s ambition, let’s take a brief look at each one.

1. Those Good Ol’ Blues of Yore

Sammie’s big show opens with a traditional brand of Delta blues. In the film’s first post-credit scene, Sammie admits that up until the vamps appeared, this was the best night of his life, and it’s easy to see why; breaking free of his father’s expectations, losing himself to the music, and burning the house down with the force of his song, this man loves music, and the crowd loves him for it.

2. Rock and Roll, Baby

It starts getting weird when a Hendrix lookalike casually wanders on stage. It makes sense that rock and roll comes next, a natural progression from the blues. The vocals blend together and we hear an unearthly swooping effect (signalling the modern era of modular sound effects) as the guitarist shreds under Sammie’s high notes.

3. Trap Hats and Hip Hop Summons DJs and Clubbers

The song pushes further into modern territory with the inclusion of straight-set trap hi-hats. Listen to the conflicting polyrhythms: the swung triplets of the guitar against the straight rhythms of the hip-hop beat. We hear rapped lyrics, see breakdancers in sweatsuits and DJ with high-tech turntables. What is going on??

4. Traditional African Tribal

The future’s had its turn, and now the past makes its grand entrance as tribal Africans in traditional garb join the festivities, tapping djembe hand drums.

5. An Unholy Gospel

Despite Sammie’s rebellion, religion remains a part of him. Even his stage name ‘Preacher Boy’ indicates this. In this vein, ‘I Lied To You’ also incorporates a heavenly gospel choir as a stark antithesis to the ‘unholy’ sounds of blues, rock, rap, and hip-hop. It all culminates together into a cacophony of musical bliss—threatening to become overwhelming as Sammie’s final note distorts into an other-wordly call into the void, one that Remmick is drawn to.

6. Chinese Xiqu

While Sinners primarily celebrates Black culture, Chinese immigrants Grace and Bo Chow are also present, and Sammie is capable of summoning the spirits of Chinese ‘xiqu’ performers, who dance their way through the juke joint wearing striking ceremonial costumes.

Yes, ‘Sinners’ Is a Musical, But Not In the Usual Way

What makes Sinners such a hypnotic cinematic experience is how deeply music is embedded within the soul of the film—not as soundtrack, but as metaphysical force. ‘I Lied To You’ and the performances at Smoke and Stack’s Juke Joint are a celebration of black music and culture in its multi-generational forms, able to transcend time and space to unite all.

Composer (and Executive Producer) Ludwig Göransson treats the art of film scoring not as background or accompaniment but as narrative scaffolding. It sonifies the ancestral, the divine, and the damned. The result is a film that sounds and feels like a séance gone horribly wrong.

As a bonus, much of the twangy, plucky guitar music in Sinners was recorded using a 1932 Dobro resonator guitar—yes, the exact same guitar Sammie Moore (Miles Caton) carries throughout the film (and uses to take half of Remmick’s face off in the climax).

As the action ramps up and Michael B. Jordan gets increasingly sweaty and unclothed, we start to hear a new genre enter the mix, one as yet untouched upon: heavy metal. As more of the party-goers are turned, crunchy power chords and frantic floor tom rolls make each punch, scream, kick and bite that much more physically visceral and mentally deranged.

Coogler and Göransson’s mashup of blues, soul and and metal isn’t mere pastiche—it’s cosmological theory in musical form. The blues, born from pain and spiritual resistance, becomes the film’s primary magic system. Metal, with its emphasis on rage and darkness, becomes its supernatural shadow twin, accompanying the violent acts of the vampires.

The tension between the two distinct sounds defines the battleground for our protagonists’ souls—particularly Sammie, who is warned away from the blues by his father, a pastor. The act of performing such powerful music is considered taboo, dangerous, even apocalyptic—and that’s where the vampires come in.

A Jig Before Judgment: The Irish Hoedown of the Damned

If Sinners‘ intense second half makes one thing clear, it’s that the supernatural isn’t always solemn—and music isn’t always redemptive. Late in the film, when the audience has grown used to the film’s spiritual invocations of Black musical ancestry, Coogler upends it all with a tonal handbrake turn: an Irish vampire hootenanny (yes, that’s a real word).

Remmick, the pallid Celtic bloodsucker in tailored tweed, has assembled his army from the very partygoers our heroes unknowingly sent to their un-deaths. A far cry from his earlier approach to the juke joint, in which his meagre trio simply plucked fiddles on the porch, asking politely to be let in, Remmick takes the film’s climax and turns it into a pagan carnival of undead revelry.

Without even a flicker of irony, actor Jack O’Connell seamlessly plunges Remmick into a rousing rendition of ‘The Rocky Road to Dublin’: an Irish folk standard from the 19th century, written by Irish poet D. K. Gavan. The alpha bloodsucker is backed by the stomping, clapping, and vampiric keening of his freshly turned clan.

It’s a ridiculous yet riveting development in this diegetic musical, and it’s held in such sincere esteem by the scoring, cinematography, and performances that you can’t help but lean forward in horror and awe.

Then comes the dance.

Yes, Remmick step dances. Pretty well, actually. His feet flick and pound in rhythmic defiance, as though shaking the dust of history off his immortal bones. What might in a lesser film play as a throwaway gag is, in Sinners, treated with the same cinematic reverence as Sammie’s juke-joint transcendence.

Though the genre-transcending ‘I Lied To You’ has become the key talking point of ‘Sinners’, and the song and scene are likely to win the film awards throughout the year, this Irish folk jig is of equal importance and quality to this music-loving moviegoer.

Just as Sammie channels the spiritual lineage of the blues, Remmick becomes a vessel for another dispossessed musical tradition—Irish folk. After a melancholy opening verse, the camera locks in, echoing the song’s 9/8 rhythm, pushing and pulling like a heartbeat on the verge of a heart attack. It’s hard not to laugh—and harder to look away as the smile fades from your face, replaced by a mesmerised kind of morbid fascination.

For the unacquainted, the 9/8 time signature sounds, simply, like a 6-legged horse gait: ba-dum, ba-dum, ba-dum. Long, short-long, short-long, short. Or, you can say, as Remmick does, ‘Rock-y road-to Dub-a-lin’ or just ‘Dub-a-lin’ 3 times, or ‘1, and-2, and-3’.

The result of this inconclusive beat is a distinctly off-kilter mood that speaks of a gleeful intoxication that Irish folk music often revels in. Add the manic stomps and cries of Remmick’s vampire clan and the sharp baritone lilt emerging from his bloodied mouth, and you have a step-dancing sleep paralysis demon that haunts its victims with its own unabashed ridiculousness.

The Irish jig distances the performers from their previous 3-part harmonies presented to Smoke, Stack, and later, Hailee Steinfeld’s multiracial Mary. Their first songs were meant to entice and seduce, to proclaim innocence and well meaning. But ‘The Rocky Road to Dublin’, while having the airs of an Irish party riverdance, is unhinged menace at its finest.

Sinners Chooses Irish and African-American Music For A Reason

Irish and African music may seem an odd choice, but there is more crossover here than most are aware. Remmick touches upon this as he speaks of Ireland’s colonisation hundreds of years ago, attempting to form a cultural connection to the plight of our Black protagonists. He makes it clear he doesn’t align with the values of his Klan-associated companions—he sees Sammie’s side of the story.

We have two folklores—two hauntologies, really—forged in the crucibles of colonial violence and diasporic grief. That they meet on the dance floor—one possessed by ancient hunger, the other by cultural bliss—isn’t just a gimmick, or an adherence to the film’s musical bones. It feels more like… a reckoning.

Coogler drawns both similarities and distinctions between the Irish and African music at the heart of ‘Sinners’; they’re two musical cultures drawn from folk traditions, powered by pulsing beats, and marginalised by those in authority. Even the step-dancing is an inherent act of rebellion, harkening back to the Penal days of Ireland, when it’s believed that children learning to step-dance adopted the now-standard stiff upper body to avoid being seen dancing through their windows. Meanwhile, blues music was known as the ‘Devil’s music’, shunned by Christian and white-society alike.

‘The Rocky Road to Dublin’, rooted firmly in 19th-century Irish music-hall satire and immigrant struggle, is about being beaten, mocked, and exiled—until fellow outsiders rally in solidarity. Remmick repeatedly weaponises that spirit to forge his own twisted kinship with the Black protagonists: a vampiric collective bound by coercion rather than freedom. His rendition channels Irish session culture and sean-nós tradition, but it’s hollow mimicry—a dark mirror to Sammie’s authentic, veil-piercing blues performance.

Remmick doesn’t offer true solidarity; he echoes centuries of cultural theft and colonisation. His performance yearns for communion, but it’s Sammie’s blues, not Remmick’s borrowed rebellion, that wields the true power.

Why Vampires? Why Blues and Jigs? Why Now?

Sinners’ strict, almost reverent adherence to the classic rules of vampire lore (the garlic, the sunlight, the wooden stakes, the being welcomed inside) threatens to lean into absurdity, but Coogler handles the antagonists with a seriousness and lack of irony that lends itself perfectly to the fears and superstitions of our protagonists.

Before Remmick and his KKK-turned couples’ true nature is revealed, the film’s subtle signposting also allows the viewer to piece it together for themselves. Once their repeated insistence on being welcomed inside verges on the ludicrous, it’s a forgone conclusion that we’re dealing with vampires. But the context doesn’t make the juke joint’s inhabitants’ situation any less tense for audiences.

I remember saying something similar regarding the mermaids and sea-gods of The Lighthouse (2019) – that monsters of myth and folklore don’t need to be reinvented to remain relevant or ‘scary’ to modern movie-goers, especially in these dramatic period pieces. They just need to be taken seriously. And the heroes of Sinners take to their wooden stakes, garlic, and sunlight with aplomb.

The traditional approach to bloodsuckers also meshes well with the cultural themes and commentary of Sinners. The film could’ve gone the other way and shied away from conventional vampire rules, but Coogler doubles down on the classic vampire lore in order to belay a message about culture and identity.

The vampires are symbols of generational rot—when generational pain festers into something immortal and inestinguishable. Vampirism—and acceptance into Remmick’s eternal hive mind—represents the easy way out. But Sammie uses his music spiritually and physically to fight vampirism, gaining true immortality. After all, it is through Sammie’s ecstatic performance that the partiers at the juke joint reached the souls of spirits long dead and yet to come, achieving real, complete unity beyond any that an age-old vampire could offer.

The combination of bloodsuckers, blues and jigs may seem a strange potion, but its one that needs to be experienced in cinemas while you still can. It’s also a cocktail especially suited to the socio-political climate we find ourselves on the other side of the 21st century’s first quarter.

Sinners, the Musical Is a Wild Ride, And All the Better For It

Sinners is not just a horror film that features songs; it’s one that is a song, stitched from the wails of the Delta, the stomp of a jig, the distorted crunch of a guitar straining against time and space. Coogler and Göransson have crafted a cinematic parable about legacy, power, and the ghosts we choose to awaken (and those we don’t).

The vampires reveal the film’s clearest truth: that cultural parasitism, no matter how eloquent its language, still leaves bite marks. While both Remmick’s step-dancing hoedown and Sammie’s soul-rending blues are rooted in rebellion, Sinners ultimately presents two visions of inherited tradition—one that leeches, and one that liberates. But Remmick understands exactly what Sammie and the twins have been through. He’s seen it too. That’s why he wants so keenly to absorb them into his pack. That’s why he hears the opening of the meta-musical portal through time, he hears this virtuoso bring the house down, and he wants in.

So, yes, Sinners is a musical—a diegetic one of the highest quality. Why? Let me put it this way with my closing words: one minute, you’re experiencing euphoric, Baz Luhrmann-esque transcendence over a blues ballad, the next, a vampire in a waistcoat is leading an Irish step dance under a blood moon. Somehow, it all makes perfect sense, and I think that’s bloody beautiful.

Enjoyed this post? Why not subscribe to the newsletter, or as I like to say, enlist in the guild? Simply add your name and email and I'll make contact when the next post is ready. Until then, cyberspace adventurer...

It’s fascinating how the film uses step-dancing and blues not just for aesthetic, but as a vehicle to unmask evil and resurrect memory. That’s a deeper musical metaphor than most horror musicals ever attempt, and it really sets *Sinners* apart as something more than just genre mashup.

Yes, the film really makes you consider music in a different way, just as it uses music much differently from traditional musicals or even just movies with songs in them.

What a fascinating genre mashup! The idea of using blues as a narrative tool to resurrect memory and confront evil is deeply compelling, especially when paired with the lively energy of Irish jigs.

For sure, it’s the contradiction of blues and jig that makes the film so sonically and visually unique. Probably the best film of the year, in my opinion.

I love how *Sinners* flips the vampire genre on its head—turning the undead into musical conduits for memory and reckoning is such a fresh take. It’s rare to see a film that uses music not just to set the mood, but to actively reshape reality within the story.

Totally, it’s such a riveting and unique genre mashup! Hats off the the whole crew who came up with it.

Using Depression-era blues and Irish step-dancing as narrative tools in a vampire film is such a bold move. It’s refreshing to see music not just scoring the moment, but actually shaping the mythos and emotional stakes of the story.

I’m glad you agree, it feels strange to say but I can’t remember another movie in recent memory that used music so effectively in the narrative.

The idea of music as a supernatural force really resonated with me—especially in a vampire context where immortality and memory are so tightly woven. It makes sense that music could be a bridge between the living and the dead.

wohh just what I was searching for, appreciate it for posting.

A diegetic vampire musical blending blues and Irish jigs sounds wild! Really intrigued by that unique sound combination, thanks for the heads-up.

That unforgettable scene where Sammie’s music literally sets everything on fire was something else