“How long have we been on this rock? Five weeks? Two days? Where are we?”

Indeed, how long has our spherical rock been floating endlessly through the void? 4 billion years? 14 billion? Is there any way to truly know when and where we are, when we have next to no point of reference for our situation in the cosmic ocean?

And, if there truly was a way we thought we could discover this forbidden knowledge, a one true light we could wield against the vast, dark vista of infinite nothingness, would we hide from it, pursue it, lust for it?

Don’t worry if this is all getting a little too existential for you – we’re going to redirect this question to the fictional characters of Thomas Wake and Ephraim Winslow, two characters in a certain two-hander film starring Willem Dafoe and Robert Pattinson as squabbling lighthouse keepers driven mad by monotony and isolation.

I am, of course, referring to the genre-defying, black-and-white, claustrophobia-inducing film The Lighthouse (2019).

Suffice to say, in attempting to explain The Lighthouse, we’re going to dig into some spoiler-occupied territory, so unless you’ve seen the film already, maybe go and watch it first, take some time to have an existential crisis, take a shower, then return for some answers.

Which Genre Is The Lighthouse? Robert Eggers’ Answer is ‘Yes.’

To explain it in a sentence, The Lighthouse is pretty much The Shining but a couple centuries older and with mermaids. An oversimplification that skims over the mythological, psychological, and historical context, but a pretty decent way of convincing your film buddy to see it with you.

But when your buddy asks, “What Genre is The Lighthouse?”, how are you going to explain that? Psychological horror? Dark comedy? Cosmic horror? Character study? How about all of the above?

There’s more in the way of morbid themes, striking dialect, set design, theatre-inspired acting choices, and literary inspirations than I could shake a lobster at, but here are some of my favourite ways in which The Lighthouse carves out its place in cinema fame.

Madness in Monochrome: Making Vintage Modern Again

Where the heck did all the colour go? The choice to make the film entirely in black-and-white was a bold one, but it absolutely works.

Cinematographer Jarin Blaschke used his background in still photography to create high-contrast images that pair extraordinarily well with the squarish 1.19:1 aspect ratio – a peculiar configuration created when sound was added to cinema, used only fleetingly between 1926 and 1932. It was eventually deemed ‘too square’ by audiences.

But this nearly square frame has been brought back for the 2019 film, resulting in stifling shots that make the cramped, damp lighthouse feel that much more claustrophobic and psychologically threatening.

It’s hauntingly reminiscent of cinema of the 1920s and 30s, particularly the German expressionist films from the early 1900s like the 1922 “Nosferatu” (which, coincidentally or not, Eggers would later remake in 2024).

Pairing perfectly with the aspect ratio and monochrome film, Eggers’ background in stage production is starkly apparent—the film’s script calls for dynamic, intense lines from its two stars, leading the audience in loops that make them feel as though they, too, are driven mad.

The psychological drama that unfolds is propelled by the archaic and almost unbearably cryptic manner of Wake’s (Dafoe’s) Coleridge-inspired dialogue.

Add to that the way the black and white medium allows each scene to feel as though it is carved from darkness rather than light, and the viewer feels as though they are transported to a century-old era of cinema, completely removed from the colours and sounds of the outside world.

The Tell-Tale Heart: Allen Poe, Coleridge, Shakespeare, and More

The dialogue and imagery of The Lighthouse pay constant homage to the works of Edgar Allen Poe; indeed, the film was originally director Robert Egger and his brother, Max Eggers’ envisioning of Poe’s unfinished short story of the same name.

Though the finished film bears little resemblance to the goings-on of the brief text, the script’s dialect and visual symbolism are deeply entrenched in the masterpieces of Poe-adjacent literary giants.

- The seagull whose death eventually and resoundingly damns Winslow to purgatory literally comes tapping on his window, or, as Poe put it, ‘rapping on [his] chamber door.’

- Director Robert Eggers referenced the works of poet Sarah Orne Jewett, in particular the caesuras, hyphenations, trochaic octameter, and mono and disyllabic words present in Dafoe’s dialogue.

- The sheer isolation of the two lighthouse keepers brings to mind the characters of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

- Shakespearean soliloquy meets Miltonian epic and Homer’s Odyssey, as The Lighthouse features invocations to sea gods and deities, as well as the homoeroticism present in the Greek epics of old.

- Take a look at Robert Taylor Coleridge’s 1834 poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner to see how its macabre, supernatural themes inform the film’s imagery, in particular, the killing of a sea bird that contains the spirit of a dead sailor.

- The terror of losing one’s self, the visions of horrific tentacles, and the forbidden, unknowable truth of the light are all straight out of the playbook of cosmic horror author H.P Lovecraft.

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to literary allusions and inspirations. I could go on (and I have), but I’ll spare you the heavy reading, for it’s time to dig deep into the film’s mythological and erotic subtext. This is where it really gets weird.

Mermaids and Myths: Playing with Fire

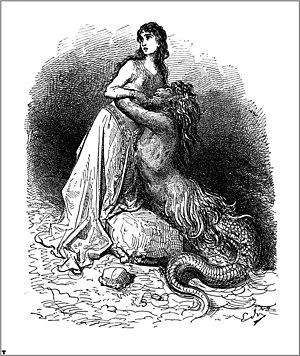

In mythology and folklore, mermaids are linked to sirens, known for enchanting lecherous men. But amid a particularly hallucinatory scene, Winslow beds (or beaches, I suppose) a mermaid, who then, mid-fornication, transforms into a crusty, horned sea god that takes the face of Wake, who seems to revel in Winslow’s repressed homoerotic desires, laughing at the shameful, forbidden joke.

In ancient myth, Proteus was a sea-dwelling shapeshifter, as unpredictable as he was wrathful. If Wake truly is some sea deity, as this scene implies, then he is the god of the lighthouse who has tasked himself with punishing Ephraim Winslow.

The presentation of classic myths (particularly those of Greek legend) is presented in a horrifying lens, yet remains faithful to past depictions, proving that you don’t need to reinvent the wheel to create scares, even in a film such as this.

In perhaps the most striking monologue The Lighthouse has to offer – and perhaps the moment when the viewer first marvels at the archaic, near-Shakespearean script – Thomas Wake (Dafoe) berates Winslow with what sounds like an ancient curse from a vengeful sea deity (either that, or he’s just really insulted that Winslow doesn’t like his cooking). Here’s just a small segment of that curse:

Damn ye! Let Neptune strike ye dead Winslow! HAAARK! Hark Triton, hark! Bellow, bid our father the Sea King rise from the depths full fowl in his fury!

Wake continues to threaten asphyxiation by slime and bilge and a fate that would leave Winslow a corpse for harpies and seagulls (Wake believes them to be the souls of dead sailors) to feed upon. He ends his rant with a proclamation that Winslow will be:

(…) swallowed by the infinite waters of the Dread Emperor himself. Forgotten to any man, to any time, forgotten to any god or devil, forgotten even to the sea, for any stuff for part of Winslow, even any scantling of your soul is Winslow no more, but is now itself the sea!

This seems like a pretty definitive turning point for Winslow’s mood and behaviour. Though the intense scene is then broken by a brief moment of levity as Winslow professes, “Alright, have it your way. I like your cookin’,” and many drunken shenanigans later occur, one doesn’t quite move on that quickly from Willem Dafoe’s otherworldly delivery. It is after this curse that things get indescribably weird, after all, and the true psychological horror begins.

Death, Discontinuity, and Desire

Some thousand words ago I compared Winslow’s character to “The Shining’s” Jack Torrence, for their mutual descent into madness and violence. But there’s something that is ultimately more terrifying about the change we see in Winslow.

There is nothing scarier than a loss of self. Cosmic horror’s real teeth don’t come from Cthulhu tentacles or eldritch gods; it’s the realisation that reality is just a thin membrane over a terrifying, alien truth, and that the only answer is madness, or a (voluntary or otherwise) state of cosmic bliss: a nihilistic acceptance that there is no other way. Such is the inevitable descent into madness in The Lighthouse.

In Erotism: Death and Sensuality, Georges Bataille states that we as individuals exist in a perpetual state of discontinuity from others, and that death removes us from this state, destroying our sense of a separate self. We then search for continuity in other experiences – namely, eroticism.

But what The Lighthouse does is unite the two characters so intimately that they destroy discontinuity with both death and eroticism.

When Winslow finally sees the light, his distorted screams ring out in pain and pleasure simultaneously. When he masturbates, he does so with pained grunts. When Winslow and Wake clash, they almost lock lips, but end up attacking each other instead.

With the lines between love and violence, sex and death so intimately tangled up in a storm of erotic confusion and animalistic frustration, the two men ultimately gain continuity by destroying their own individual senses of self.

After the murder of Wake, Winslow finally ascends the lighthouse to the hidden light. At this point, his thought process is best left to the psychoanalysts to figure out. Suffice to say, he’s not thinking straight. His desire for the light can be explained by the film’s disturbing eroticism; exterior shots of the lighthouse make it clear that the two men are literally living inside a giant phallus, with the uppermost room where the light is kept secret as the figurative and literal head of the shape.

The light is an object of sacred ecstasy and horror, one that Wake repeatedly bathes in and pleasures himself to. Meanwhile, Winslow’s masturbatory material consists of a mermaid figurine, amidst flashes of a real mermaid washed upon the shore and a blonde male lumberjack. When finally granted the chance to observe the light, Winslow is enraptured with pleasure and terror alike.

The above shot evokes 19th-century painter Sascha Schneider’s Hypnosis, as Wake reveals to Winslow a seductive, terrifying truth, with Wake acting as an object of both desire and hatred.

Of the homoerotic and abusive nature of the relationship between Wake and Winslow, Pattinson said, “In a lot of ways, he sort of wants a daddy.” Way to break it down for us, Rob, but it’s true.

The relationship between the two men can be read through an Oedipal lens, culminating in a bizarre role reversal where Winslow rebukes the dehumanisation of Wake’s derogatory insults by forcing him to walk on all fours like a dog.

At this point, Winslow is no longer able to distinguish sex from violence, love from hate. The two men enter an erotic relationship by default, whether out of madness, sexual attraction or plain loneliness.

All Work and No Play…

Doldrums. Doldrums. Eviler than the Devil. Boredom makes men to villains, and the water goes quick, lad, vanished. The only med’cine is drink. Keeps them sailors happy, keeps ’em agreeable, keeps ’em calm.”

A much simpler and concise explanation of the cabin fever plaguing the lighthouse keepers occurs in Stanley Kubrick’s film “The Shining”, as Wendy finally discovers that Jack hasn’t done a lick of writing all winter, instead typing the mantra “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy” countless times.

It’s hard to say how any of our minds and bodies would respond to the intense isolation the characters of these stories endure. Add to that the heavy implications of supernatural evils at work, and it’s no wonder they snapped.

In both horror films, the main character seemingly – through prolonged isolation and boredom – unlocks the unknown dark side of one’s personality that you may know as ‘the Shadow’ – a concept posited by psychologist Carl Jung.

Basically, the shadow is made up of whatever it is we don’t want to know about ourselves. But with nothing else to do and only grim surroundings and thoughts for company, it seems inevitable that these isolated characters should discover, and be consumed by, their shadows.

French inventor and physicist Blaise Pascal said it best: “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.”

And while, yes, a lot of people nowadays could actually greatly benefit from putting away the blue-light devices and sitting quietly, that’s on a completely different scale to the grim environment of The Lighthouse, where the endless peeling off all the layers of one’s self can only end with the darkest of results.

‘I Tend the Light’ – What Really Happened Up There?

In the film’s climax, Pattinson’s Winslow finally gets hands-on with ‘The Light’, the object of his and Wake’s desire, a secret power akin to the fire that Prometheus seeks in the Greek myths of old. In a nightmare-fueled scene, he laughs and screams madly, convulsing with the gift of the light before tumbling down the stairs.

Conjecture abounds from the ambiguous final shot of the film: Ephraim Winslow (Thomas Howard) laid out naked on the coast, his guts being pecked out by seagulls. Some of the more popular theories posit that:

Young and Old are One and the Same.

By far the most popular theory, the concept is supported by the fact that in the script, Dafoe and Pattinson’s characters are referred to as ‘Old’ and ‘Young’, and the way in which Pattinson’s mannerisms become more like Dafoe’s towards the end of the film.

This theory aligns with a psychological reading of the film that includes the Jungian idea of the Shadow (the dark side of an individual’s psyche, often released by intense psychological trauma or duress), for in many ways both characters can be identified as the shadow of the other on some level.

Wake (Dafoe) was never there.

There is, however, a Proteus-like deity that welcomes Winslow (Pattinson) to what is essentially purgatory, an in-between state worse than death. The entire movie encompasses a delirious, mad Winslow’s dying thoughts as he is marooned and left to die.

Indeed, the final shot chooses to exclude the titular lighthouse, and implies that either Winslow crawled out of the building after falling down the stairs, his mind torn to shreds by whatever it is he saw and felt in the forbidden light, then stripped naked and presented himself to the hungry gulls – or that the lighthouse was never there and he has really been lying on the coast the whole time, haunted by visions of seductive mermaids and ancient terrors.

Wake is Proteus, Winslow is Prometheus.

With numerous visual and scripted references to the classic myth of Prometheus, it’s almost too easy to paint The Lighthouse as a mind-bending retelling of the tale. Yet the similarities cannot be denied: Winslow murders Wake and goes upstairs to steal the light (fire), yet is smote down and left for dead, with seagulls pecking out his insides.

Just like Prometheus, he betrayed the god(s) with his actions, and must pay the price – perhaps for eternity.

Wake is a rambling version of Proteus, an old, prophetic sea god, who acknowledges his connection to his father, Poseidon, and brother, Triton, in one of his many salty rants.

In this mythological reading of the film, Wake acts as a harbinger of Winslow’s doom, warning him of ‘Protean forms’ that scorch eyes ‘with divine shames and horror’. Winslow ignores Wake, who is portrayed as the ‘god’ of the island, and so is punished for his betrayal.

Aliens and Gods, Oh My!

Something that may stand out to you at the end of the film is the design of the light: a Fresnel lens, first invented by Augustin Fresnel in the 1820s. The striking visual design looks almost futuristic, but is a fairly accurate depiction of the invention that has saved so many millions of vessels from shipwreck since.

Something about the way the light slides open like Pandora’s Box, tempting Winslow to reach in and touch it, speaks of a greater force than simple physics and electromagnetic radiation. Is it, then possible that this truly is some form of experiment or simulation, and that the doors of the coveted light is the doorway to freedom or salvation?

Who, then, is the god or being keeping these two souls trapped on this craggy rock? An eldritch alien, older than humanity itself? A mischievous deity toying with the sanity of both men?

Who’s Doing the Gaslighting, Here?

It’s difficult to say who’s more mad by the end of the film. The film heavily signposts that, at least from the point the characters resort to drinking turpentine to get rip-roaring drunk (the only thing there is left to do after all their rations are ruined), everything that occurs is a product of their deteriorating mental conditions.

These circumstances make it difficult to believe anything seen on screen, especially from Winslow (Pattinson)’s point of view, through which we are privy to visions of eldritch tentacles and seductive (and violent) mermaids.

Additionally, Wake continually gaslights Winslow by claiming he hasn’t completed jobs properly; and after Wake chases Winslow with an axe and destroys the only boat on the island, he claims that Winslow was the one who chased him.

But when all this is said and done, there’s no doubt that this island is hell for both men, a form of Stygian punishment for their sins. One of the more spine-chilling quotes comes just after Winslow drunkenly reveals why he took the lighthouse job—that he left his previous foreman for dead and took his name, that his real name is Thomas Howard.

It’s notable that prior to the revelation, Wake warned Winslow not to say anything. After the admission, Wake repeatedly croons, “Why’d ye spill yer beans?”, and Winslow’s fate is sealed as a menacing, hallucinatory vision proceeds.

What Is The Lighthouse All About, Anyway?

If you’ve finished the film and immediately Googled The Lighthouse Explained or What Happened in The Lighthouse, you may be missing the point (although it probably brought you here, for which I thank you). Quite a lot did happen in the film, but just as much didn’t.

We have no concrete knowledge of what is real or not or even who and what the two characters are – are they simply a couple of 19th century lighthouse keepers, or manifestations of age-old mythical figures Proteus and Prometheus?

Regardless of the conclusions your viewing left you with or how well I explained the various meanings of The Lighthouse, the story itself was never meant to be straightforward. Focus instead on how the film made you feel. Terrified, ashamed, curious, sullied… a bit like Robert Pattinson’s face just below, I imagine…

Lessons of The Lighthouse

At times it can be all too easy to retreat into our own personal lighthouses, the dark, hidden places where the rest of the world may as well not exist. Where none of the threats of the world can reach us. But it’s comforting to know that films like The Lighthouse can bring us together in bewilderment, terror, and pure entertainment.

So, whatever you took from the film, whether you liked it or not, just be glad that it made you do two things we so often don’t have time for these days: think and feel.

Enjoyed this post? Why not subscribe to the newsletter, or as I like to say, enlist in the guild? Simply add your name and email and I'll make contact when the next post is ready. Until then, cyberspace adventurer...

Wow, this article! So well written, so nuanced, and adds so much value to a viewing of this film. I’m already planning my rewatch after reading this!